The rest of this section is meant to be an introduction for someone who is unfamiliar with the concept of fantasy role playing. More experienced readers may want to skip this material, but the novice should read them carefully.

The rest of this section is meant to be an introduction for someone who is unfamiliar with the concept of fantasy role playing. More experienced readers may want to skip this material, but the novice should read them carefully.The Rolemaster Standard System (RMSS) is ICE’s complete fantasy role playing system, combining four basic parts: the Rolemaster Standard Rules, Arms Law, Spell Law, and Gamemaster Law. The RMSS is suitable for experienced gamers who want guidelines and material to inject into their own existing game systems and world systems, as well as for those who are looking for a realistic yet playable fantasy role playing system. It contains complete rules for handling most of the situations that arise in FRP games. A variety of tables and charts add a great deal of flavor and detail to a game without significantly decreasing playability.

The RMSS is provided in a convenient 3-hole punch format with a system of access tabs for easy reference. So as future optional guidelines and rules are released, a GM can easily update his world’s rules system with the material he deems appropriate.

The Rolemaster Standard System’s four basic components are:

The Rolemaster Standard Rules (RMSR) provides all the guidelines and rules needed to play Rolemaster. Its primary parts are concerned with character definition, character design, performing actions, and outlining the Gamemaster’s tasks.

Arms Law (AL) provides the melee and missile combat tables and charts for the RMSS, while the Rolemaster Standard Rules fully describes their use within the system.

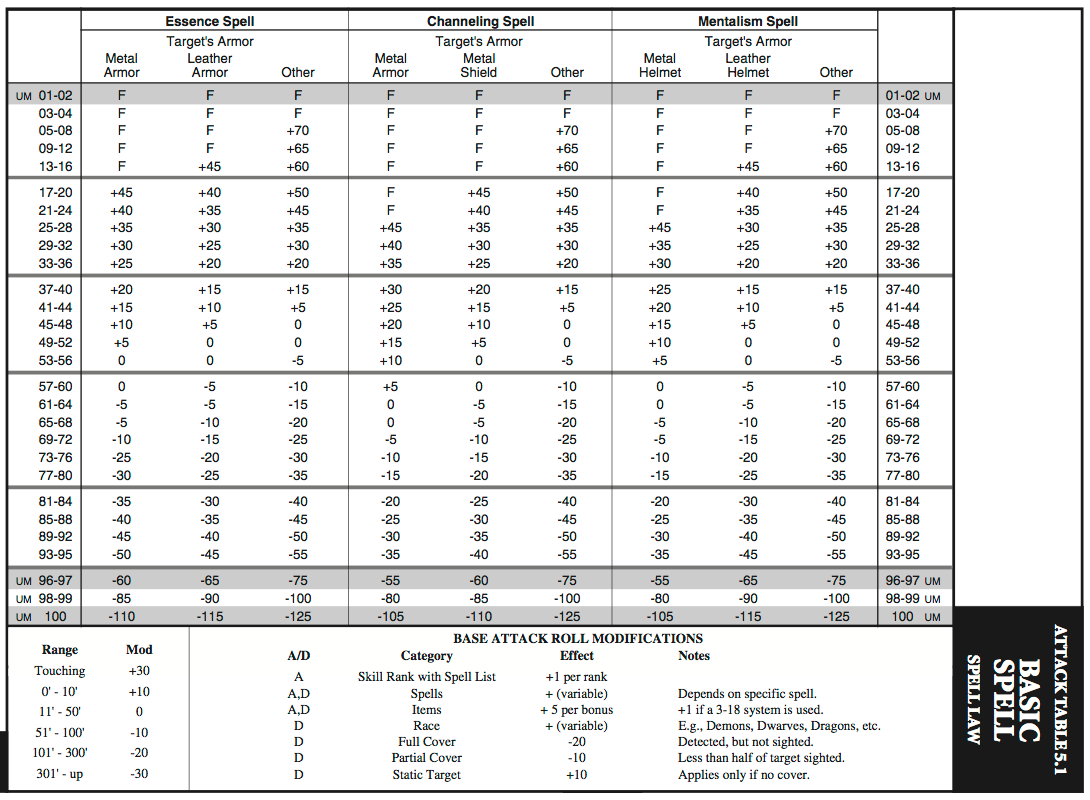

Spell Law (SL) provides the spell lists and spell combat tables and charts for the RMSS, while the Rolemaster Standard Rules fully describes their use within the system.

Gamemaster Law (GML) provides the detailed guidelines and material that a Gamemaster needs to run a role playing game in general and specifically using the RMSS.

These four products allow a Gamemaster to expand an existing system by gradually inserting components. Such a process can increase the variations and options available to the Gamemaster and the players without forcing an abrupt transition to a new game system. A more detailed description of each component system is presented in Section 1.3.1.

The rest of this section is meant to be an introduction for someone who is unfamiliar with the concept of fantasy role playing. More experienced readers may want to skip this material, but the novice should read them carefully.

The rest of this section is meant to be an introduction for someone who is unfamiliar with the concept of fantasy role playing. More experienced readers may want to skip this material, but the novice should read them carefully.

Note: For readability purposes, Rolemaster uses standard masculine pronouns when referring to persons of uncertain gender. In such cases, these pronouns are intended to convey the meanings: he/she, her/his, etc.

The easiest way to understand a role playing game is to think of it as a work of fiction such as a novel or a play or a movie. In a novel the author determines the setting of the novel along with the actions of all of the characters and thus the plot. In a role playing game, the author (called the Gamemaster) determines the setting and some of the basic elements of the plot. The actions of the characters (and thus part of the plot) are determined during the game by the game “players” and the Gamemaster. Each “player” controls the actions of his “player character” or alter ego, while the Gamemaster controls the actions of all of the other characters (called non-player characters). Thus each player assumes the role of (role plays) his character and the Gamemaster role plays the non-player characters. A fantasy role playing game is a “living” novel where interaction between the actors (characters) creates a constantly evolving plot.

The Gamemaster also makes sure that all characters perform actions which are possible only within the framework of the setting that he has developed (his “fantasy” world). In a sense, the Gamemaster acts as a referee. This is where the “fantasy” part and the “game” part come into the definition of a fantasy role playing game. A Gamemaster creates a setting which is not limited by the realities of our world; thus, the setting falls into the genre of fiction known as “fantasy.” However, the Gamemaster commonly uses a set of “rules” which define and control the physical realities of his fantasy world. Using these rules turns the role playing “novel” into a game.

Thus, a fantasy role playing (FRP) game is set in a fantasy world whose reality is not defined solely by our world, but instead is defined by a set of game rules. The creation of the plot of a FRP game is an on-going process which both the Gamemaster and players may affect, but which neither controls. The plot is partially determined along with the setting, but it is heavily influenced by the interaction of the characters with one another and and random events.

Thus, a fantasy role playing (FRP) game is set in a fantasy world whose reality is not defined solely by our world, but instead is defined by a set of game rules. The creation of the plot of a FRP game is an on-going process which both the Gamemaster and players may affect, but which neither controls. The plot is partially determined along with the setting, but it is heavily influenced by the interaction of the characters with one another and and random events.

Since fantasy role playing is a game, it should be interesting, exciting, and challenging. One of the main objectives of a FRP game is for each player to take on the persona of his (or her) player character, reacting to situations as the character would. This is the biggest difference between FRP games and other games such as chess or bridge. A player’s character is not just a piece or a card; in a good FRP game, a player places himself in his character’s position. The Gamemaster uses detailed descriptions, drawings and maps to help the players visualize the physical settings and other characters. In addition, each player character should speak and react to the other players as his character would. All of this creates an air of involvement, excitement, and realism (in a fantasy setting of course).

The Gamemaster has been described as “author” of the FRP game; actually, he functions as more than this. The Gamemaster not only describes everything which occurs in the game as if it were really happening to the player characters, but he also acts as a referee or judge for situations in which the actions attempted by characters must be resolved. The Gamemaster has to do a lot of preparation before the game is actually played. He must develop the setting and scenarios for the play of the game, using the game rules and material of his own design (or commercially available play aids). Until the players encounter certain situations during play, some material concerning the setting and the scenario is known only to the Gamemaster. In addition, the Gamemaster plays the roles of all of the characters and creatures who are not player characters, but still move and act within the game setting, affecting play.

Each player develops and creates a character using the rules of the game and the help of the Gamemaster (for the character’s background and history). Each player character has certain numerical ratings for his attributes, capabilities and skills. These ratings depend upon how the player develops his character using the rules of the game. Ratings determine how much of a chance the character has of accomplishing certain actions. Many of the actions that characters attempt during play have a chance of success and a chance of failure. Therefore, even though actions are initiated by the Gamemaster and the players during the game, the success or failure of these actions is determined by the rules, the characters’ ratings, and the random factor of a dice roll.

Finally, a fantasy role playing game deals with adventure, magic, action, danger, combat, treasure, heroes, villains, life and death. In short, in a FRP game the players leave the real world behind for a while, and enter a world where the fantastic is real and reality is limited only by the imagination of the GM and the players themselves.

This section provides an overview of the some of the key concepts and mechanisms of the Rolemaster Standard System. It also summarizes some of the key differences between this edition of Rolemaster and earlier editions, and it provides an overview of the RMSS and the RM product line. Finally, this section presents some definitions of some commonly used key terms along with the RMSS calculation and dice rolling conventions.

This section is meant to serve as a summary for and introduction to some of the key features of the RMSS. Some of the major factors that separate the RMSS from other FRP systems will be briefly described here. This discussion should be enough to allow many experienced fantasy role players to get the basic ideas behind this system, then each section (or product) dealing with a specific feature can be for details.

The basics of the RMSS are relatively simple to master. It is designed for those acquainted with FRP in general, or for those interested in a flavorful, detailed set of guidelines—not rules. The RMSS is intended for GMs who may wish to pick and choose their some of the parameters that define the environment of their game. ICE hopes that GMs will feel free to build upon the foundations provided.

The Rolemaster Standard System is designed to provide both the Gamemaster and his players with tremendous detail and flexibility in character development and the resolution of a wide variety of actions and activities.

The RMSS also provides a unique approach to the statistics that define a character’s physical and mental attributes (i.e., stats). Under these guidelines each stat is quite important, and no one or two stats clearly dominate. Rarely will a character be without flaws or a “chink in his armor.” A character must choose his strengths and weaknesses. In the RMSS there are 10 stats, each represented by a number between 1 and 100 (1-100). They provide detail and flavor and remain relatively simple to work with.

The stats include 4 physical characteristics: Strength, Constitution, Quickness, Agility. They also include 4 mental characteristics: Intuition, Empathy, Memory, Reasoning. Finally, there are two stats included that represent characteristics partially mental and partially physical: Presence, Self Discipline. These stats are described in detail in Section 5.0. Each stat may affect the ability of the character to perform specific actions; this is discussed in Section 5.4.

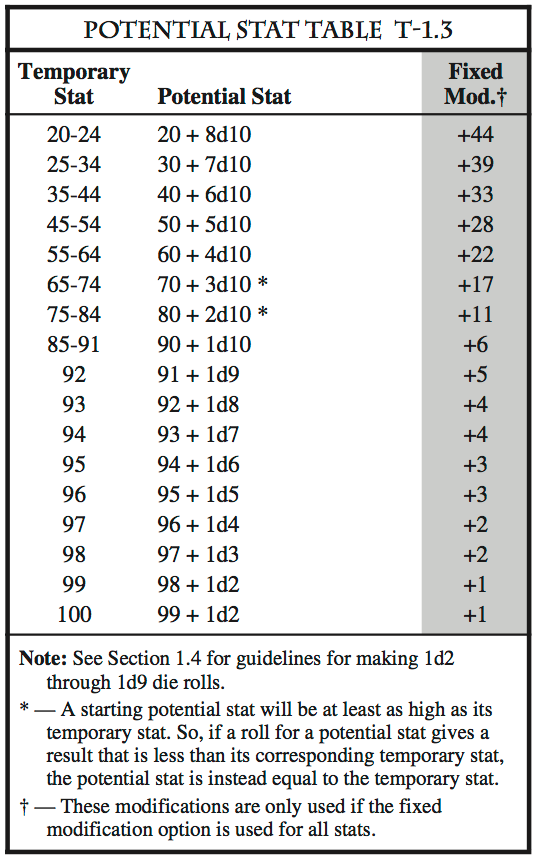

Each stat has two values. The potential (“ultimate”) value (genetically) that the character’s stat can obtain. The temporary value represents the value of the characteristic’s current level. The temporary stats can rise (due to character advancement and other factors) and fall (due to injury, old age, etc.). However, the potentials rarely change. Of course, the temporary stat for a particular characteristic can never be higher than the potential for the same characteristic. For example, a character could have a temporary Strength of 80 and a potential of 92; and the 80 would be his effective Strength for combat purposes (circumstances could raise or lower the 80 but never above 92). This feature is described in detail in Sections 5.1 and 12.0.

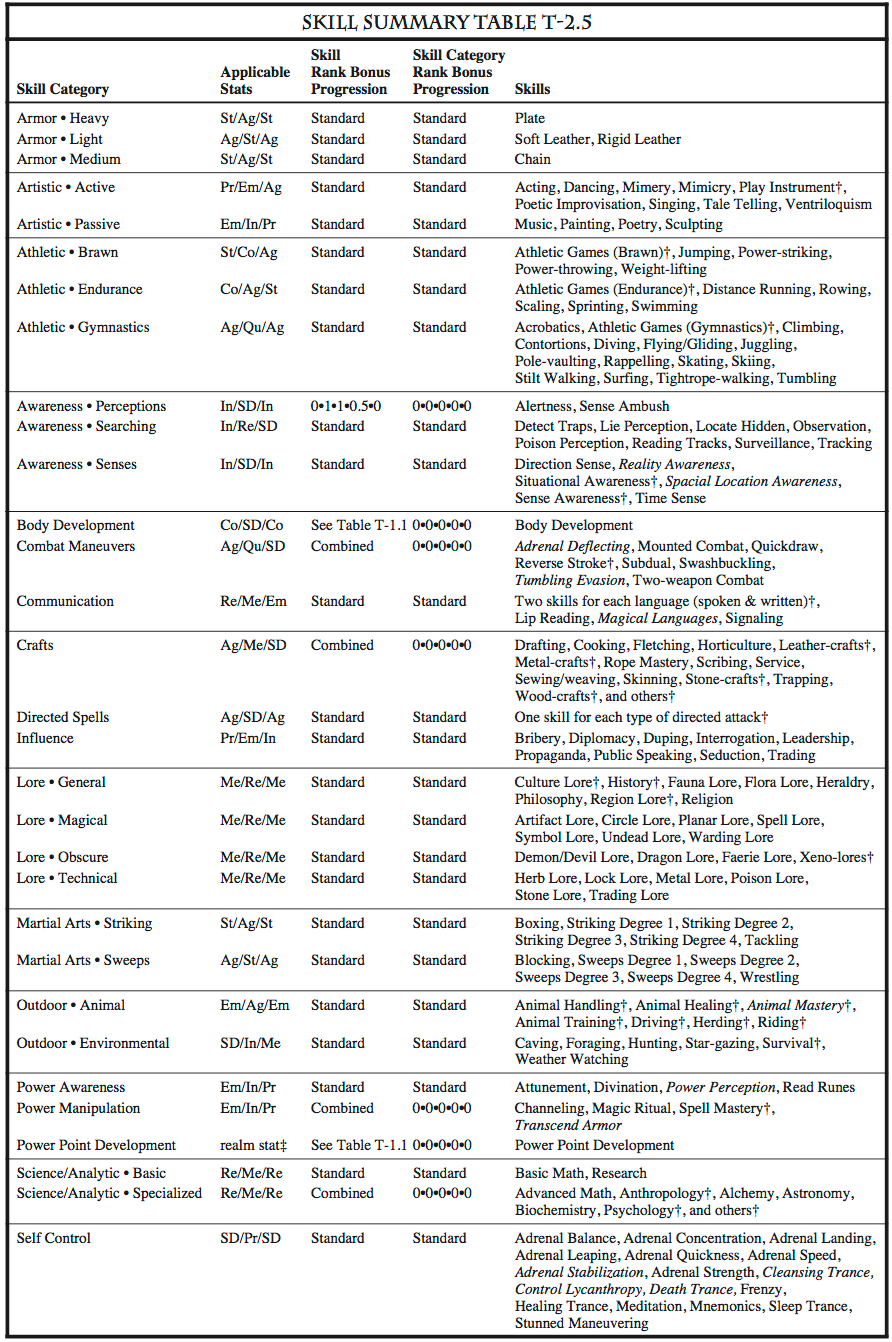

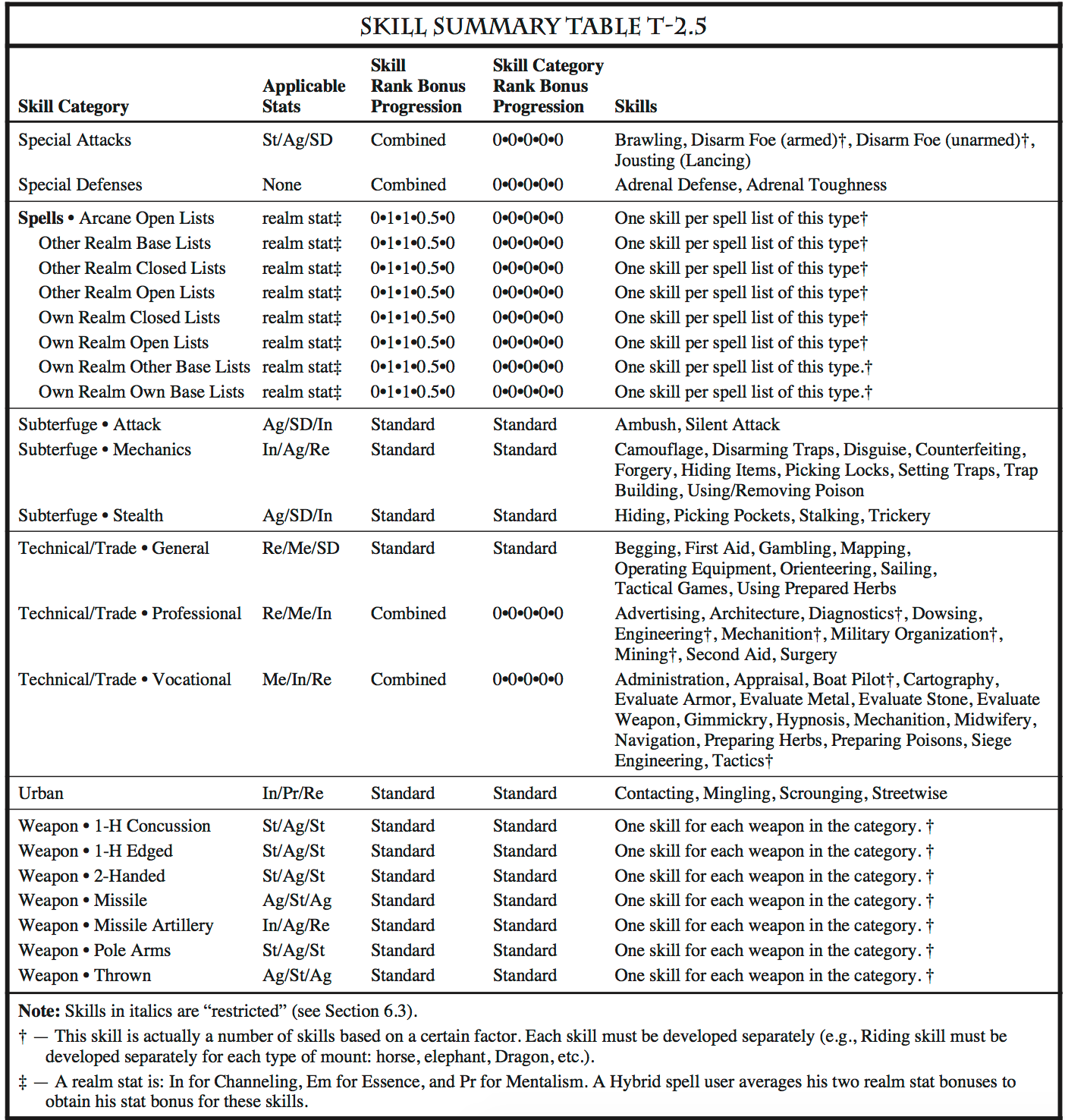

As a character advances in levels he develops and trains in certain abilities called skills and skill categories. His capability (i.e., rank) in each skill and skill category affects his chances of accomplishing certain actions and activities (e.g., fighting, maneuvering, spell casting, etc.). The key features of skills in this system are:

Each skill is grouped with other similar skills in a skill category. Both the skill and its skill category affect his chances of accomplishing certain actions.

Any character may develop any skill and skill category regardless of profession. However, depending upon the specific character’s training early in life, certain skills and skill categories require more or less effort relative to other characters. How much effort is required to develop a skill or skill category depends upon the profession chosen by the player.

Based upon the values of certain stats (Section 15.0), each character has a total amount of “effort” to devote to skill and skill category development at each level.

Each character has complete freedom in how to allocate his “effort” among the various skills and skill categories he decides to develop. Development costs will be the same for characters of the same profession and will tend to reduce the degree of variation. Yet, this “cost effectiveness” will direct development only along vaguely similar lines.

The skills and skill categories are the ones required by normal play, and a Gamemaster can easily add more if his specific game requires others. Skills are discussed in great detail in Section 6.0 and Appendix A-1.

Each character has a profession which reflects his training and inclinations in early life. A profession dictates the ease in which a particular skill or skill category may be developed, but it does not generally act to prohibit development. Thus, a player is allowed to enhance his abilities in certain skill areas which would not be accessible to his profession under other systems. Only the “cost” in time and lost opportunities in “easily developed skills” act to bias the selection process.

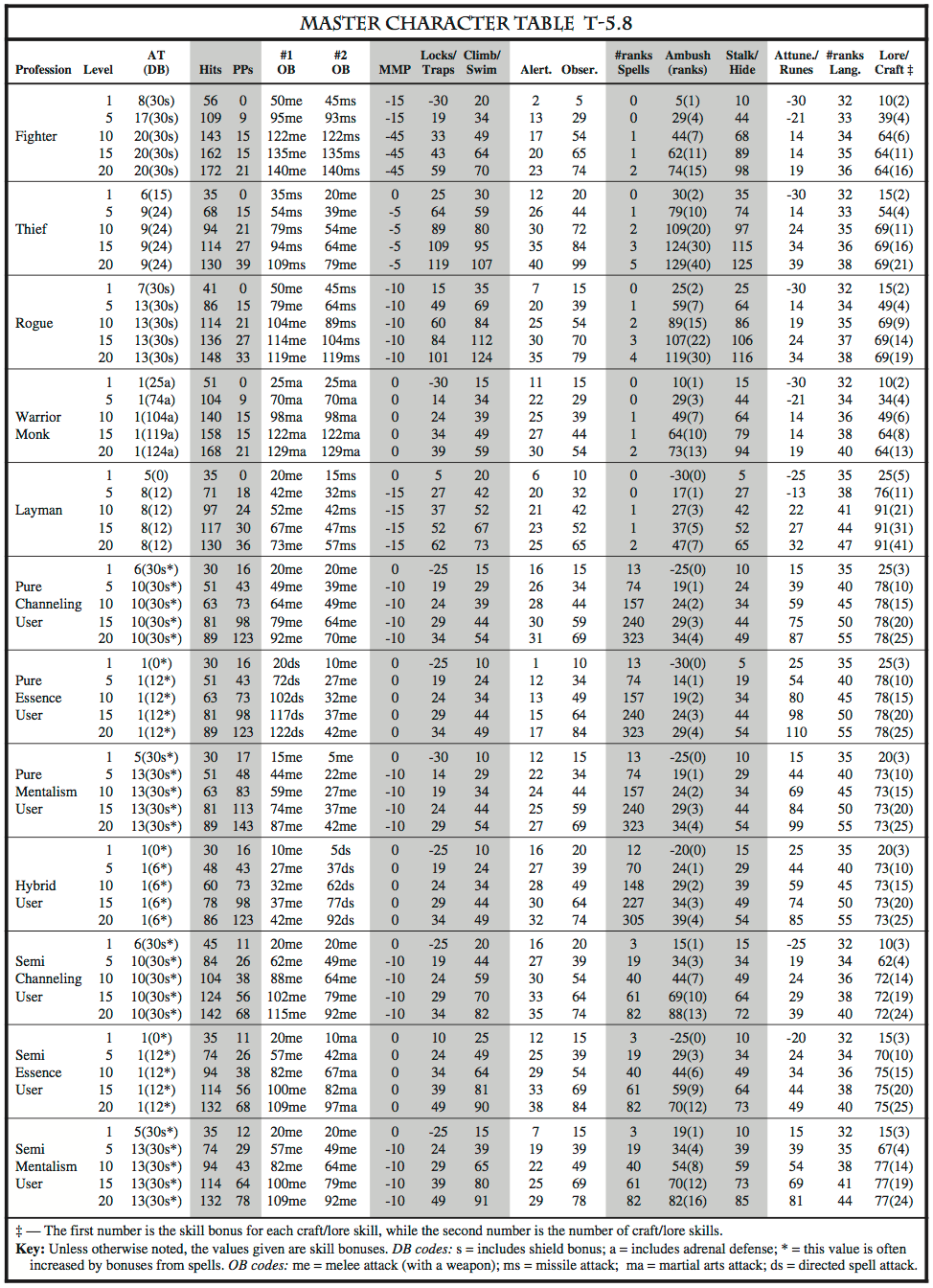

Each profession requires different “efforts” to develop each individual skill. For example, in order to gain a certain expertise in using a sword, a Fighter might only expend 20% of the effort that a Magician might: this is because a Fighter is trained in physical activities (fighting in particular), while a Magician has spent much of his early life studying spells. However, the effort required for the same Fighter to learn to cast a spell might be 20 times that required of a Magician, and he would never be very effective with it. Twenty different professions are provided and discussed in detail in Section 4.0 and Appendix A-4.

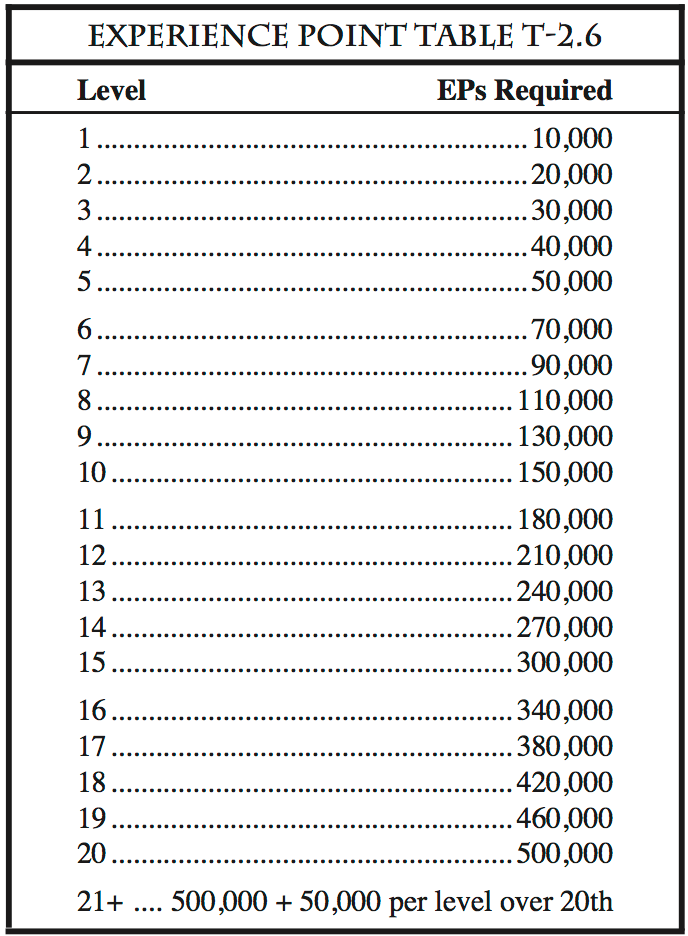

Each character while adventuring will reach stages of development called experience levels (or just “levels”). At each new level the character becomes more powerful and skillful in his chosen areas of expertise. Ideally, for realism, the character would develop after each activity or experience. However, this is extremely difficult to handle in practice. It necessitates stopping action in the game, performing bookkeeping, calculating the value of the experience, and determining what the character learned. Thus, we limit these factors by allowing a character to develop only at discrete intervals called levels (this factor is common to many FRP systems). Levels are discussed in detail in Section 7.0.

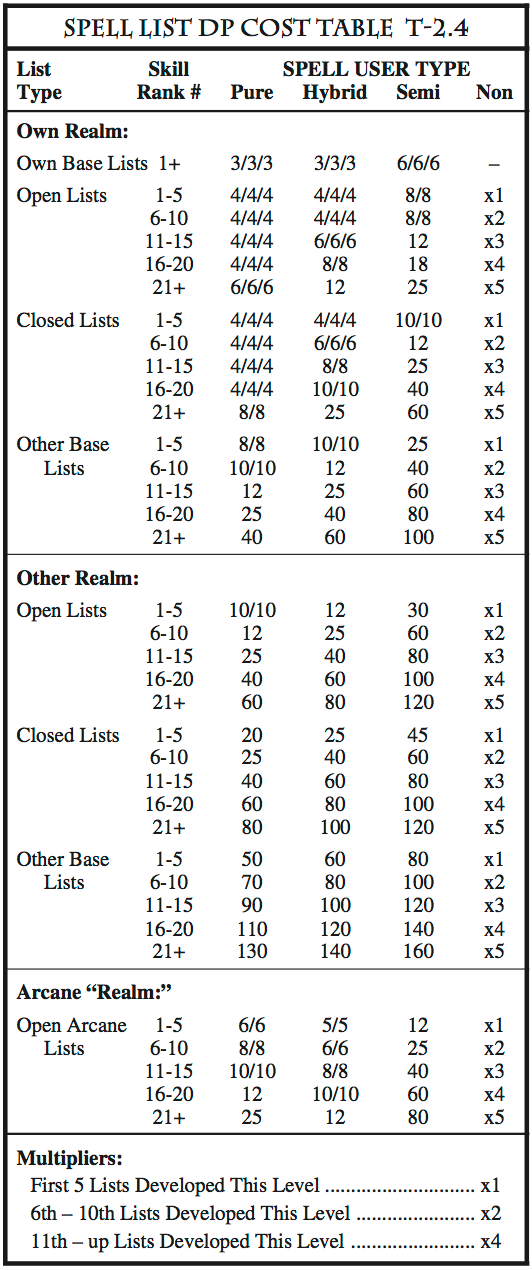

It is often desirable to provide each character with certain factors that make him (or her) unique. This system already does this to a certain extent: 20 professions and complete freedom in skill development. We also provide a variety of other suggestions, including: 16 detailed cultures/races, role traits, equipment, detailed personal backgrounds, background options, training packages, talents, special items, hobbies, etc.

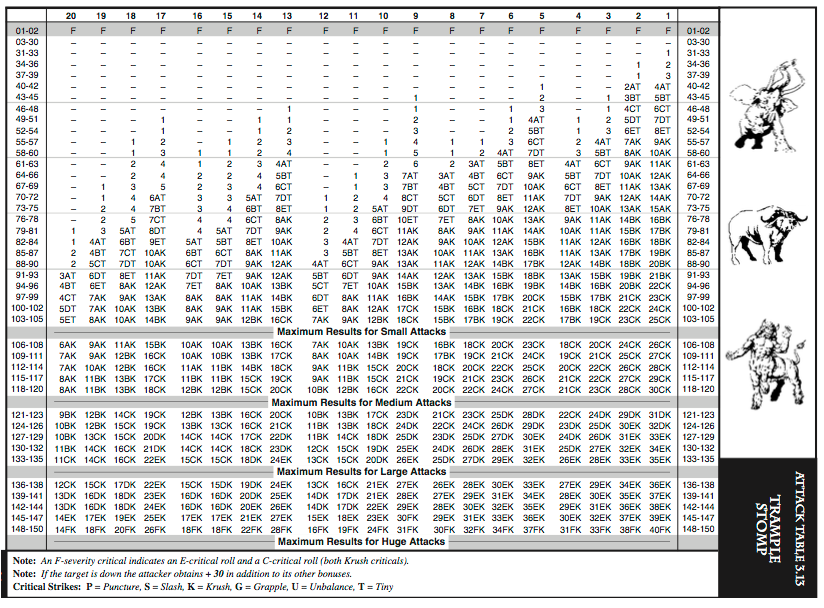

Arms Law applies the RMSS’s unique system for handing attacks to melee and missile combat. Its key features include:

A fantasy medieval melee and missile combat system with individual attack tables for twenty-nine weapons and statistics for dozens more.

Thirteen attack tables that integrate the size, instincts, and fighting patterns of a wide variety of animals, monsters, and practitioners of the martial arts.

Twelve critical strike tables that give specific, detailed damage descriptions for a variety of different types of attack results: slashing, puncturing, crushing, grappling, unbalancing, etc.

Two fumble tables that gives specific, detailed descriptions of the results of various types of weapon fumbles and attack failures.

One of the basic aspects of the RMSS is the use of spell lists and experience levels (or just levels). The ability to cast and learn spells is closely tied to a character’s level.

Spells are grouped into lists. A spell list is an ordering of spells based upon their level, intricacy, and potency. All spells in a list have common characteristics and attributes, although each may have vastly different effects and applications. Spell lists are grouped into categories based upon professions and realms of power (Channeling, Essence, and Mentalism). There are over 2,000 spell descriptions organized into 186 spell lists divided into:

1 set of “open” spell lists for each realm of power (i.e., spell lists that are learnable by characters in any profession of the realm and even by some professions outside the realm)

1 set of “closed” spell lists for each realm of power (i.e., spell lists are learnable by most characters who cast spells from the realm)

15 sets of professional “base” spell lists (i.e., a set of base spell lists are usually learnable only by characters of a specific profession)

1 set of “evil” spell lists for each realm of power (i.e., spell lists usually learnable only by “evil” characters)

3 sets of “other” professional “base” lists (i.e., spell lists associated with non-standard professions).

In addition, Spell Law uses the RMSS’s unique system for handing attacks using: critical strike tables (for heat, cold, electricity, etc.), a spell failure table, a resistance roll table, and a variety of spell attack tables.

Gamemaster Law is an aid for those who wish to create and employ an alternate world setting for their fantasy role playing game. It is designed to give Gamemasters an idea of the essential elements of a fantasy realm, and provides ways to develop a rich, consistent foundation upon which to build as their campaign progresses. It also provides a wealth of material that can help a GM handle difficult and unusual situations that can arise in a FRP game. Some key features include guidelines for:

Determining what type of game to run based upon the types of players available and the GM’s personality and skills.

Designing exciting and intriguing stories, NPCs, and backgrounds; and, letting them evolve to create an everchanging world for adventuring.

Enhancing the enjoyment of gaming sessions.

Tournament gaming and on-line gaming.

Using RMSS mechanisms for very specific situations: commerce & trading, healing, diseases, poisons, equipment, etc.

This section summarizes some of the key differences between this edition of Rolemaster and earlier editions. This material assumes that the reader is familiar with the earlier editions of RM.

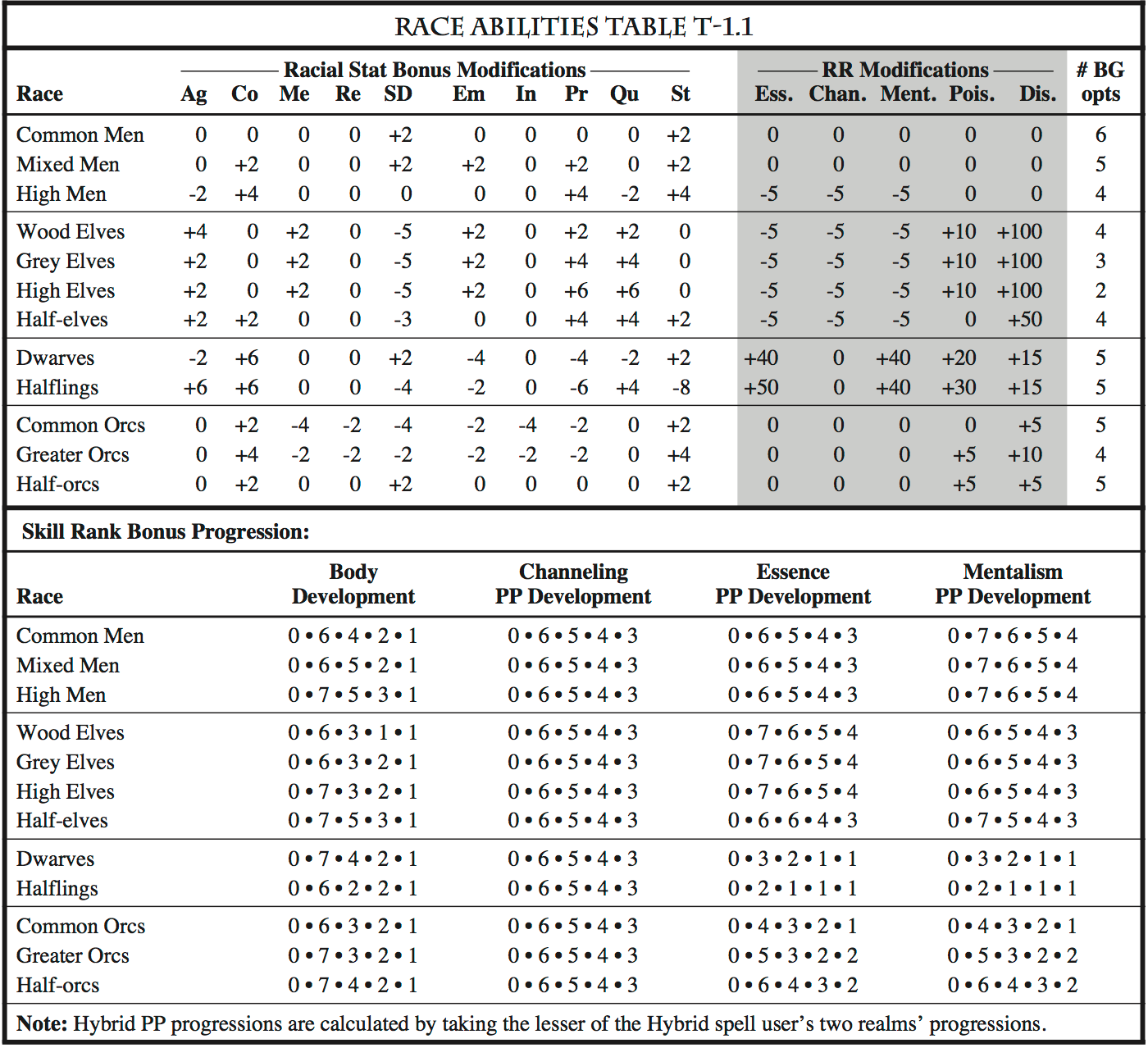

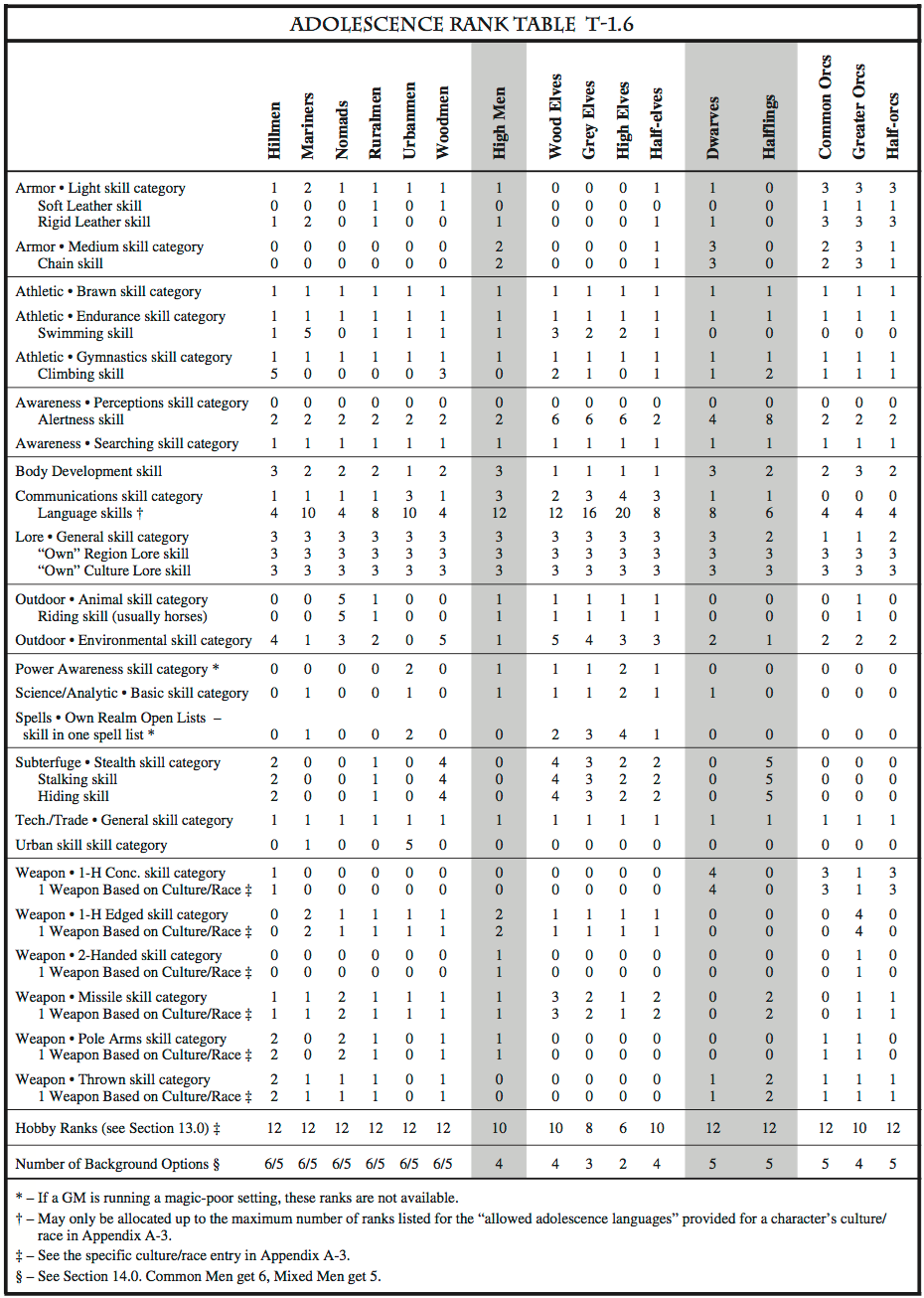

Races & Cultures — Mixed Men and Half-orcs have been added. High Elves have been renamed to Grey Elves, Fair Elves to High Elves, Normal (Lesser) Orcs to Common Orcs, and Orcs (Greater) to Greater Orcs. Trolls are no longer included as potential characters in the RMSS. In addition, each Common Man and Mixed Man character belongs to one of six Cultures.

An extensive, one-page description of each race and culture is provided in Appendix A-3. Many of the system parameters for the races differ from the old values (e.g., SD stat mods for Elves are lower, there are new, race-specific skill rank progressions for Body Development and Power Point Development, etc.).

Professions — New: Layman (the old No Profession), Dabbler (an Essence Semi spell user), Magent (a Mentalism Semi spell user), and Paladin (a Channeling Semi spell user). The Healer is now a Channeling-Mentalism Hybrid spell user), and the Alchemist, Seer, and Astrologer are not included in the RMSS.

Each Hybrid spell user has three prime requisites (stats)— its two realm stats and Self Discipline (Healer: In/Pr/SD, Mystic: Em/Pr/SD, and Sorcerer: Em/In/SD).

A profession no longer has level bonuses associated with it, instead, it has fixed profession bonuses. An extensive, one-page description of each profession is provided in Appendix A-5.

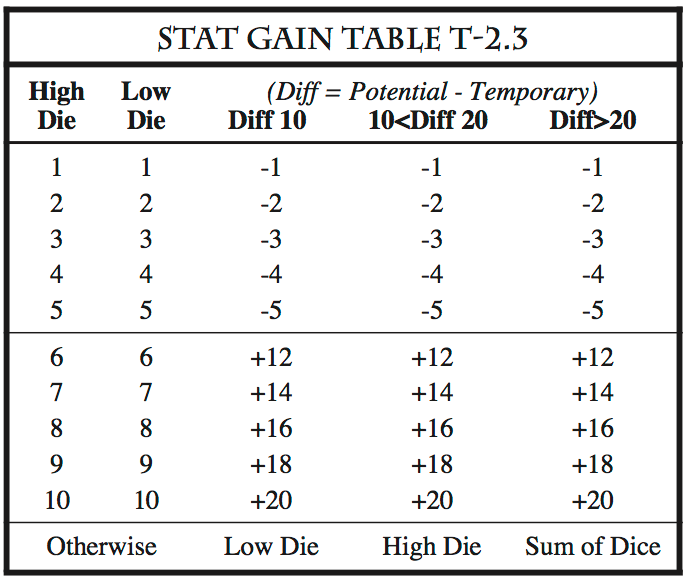

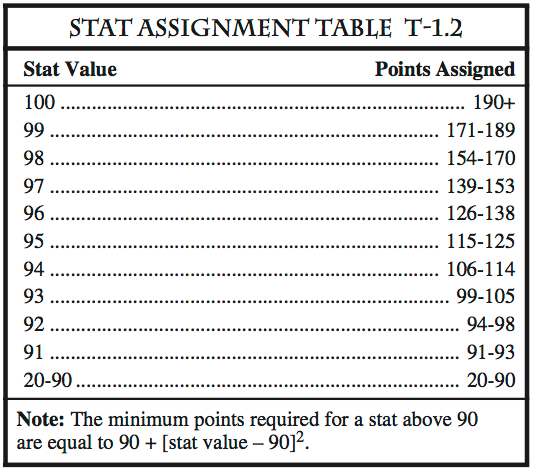

Stats — Temporary stats are now generated by assigning 600 + 10d10 points. This is a one-to-one assignment for stats under 91, with a increased cost for stats above 90. Each potential stat is determined by rolling a number of dice related to the difference between the temporary and the potential. Stat gain rolls are also handled in a slightly different manner.

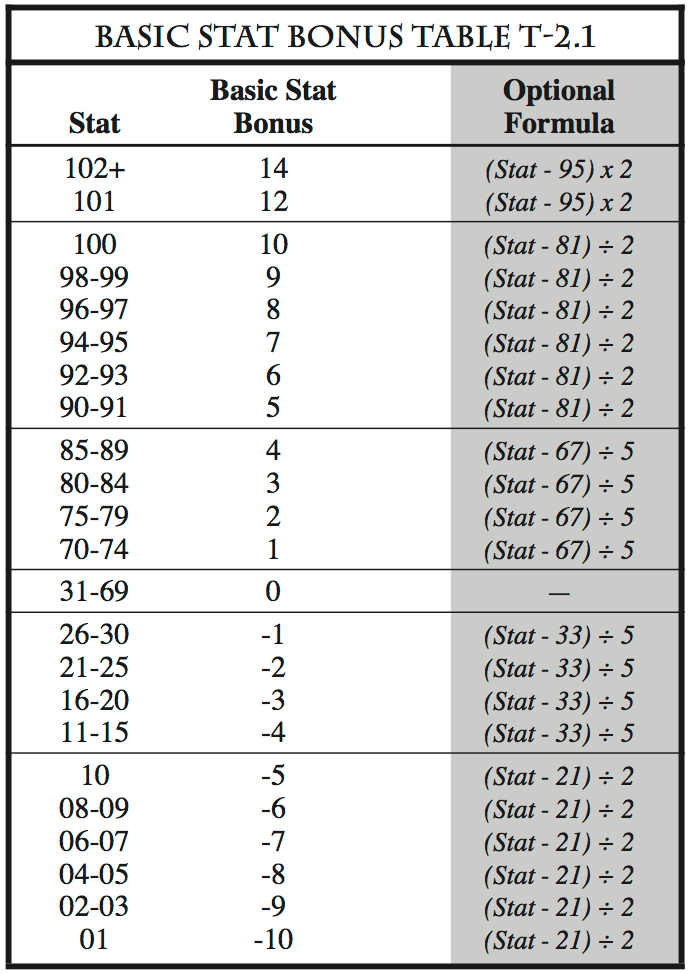

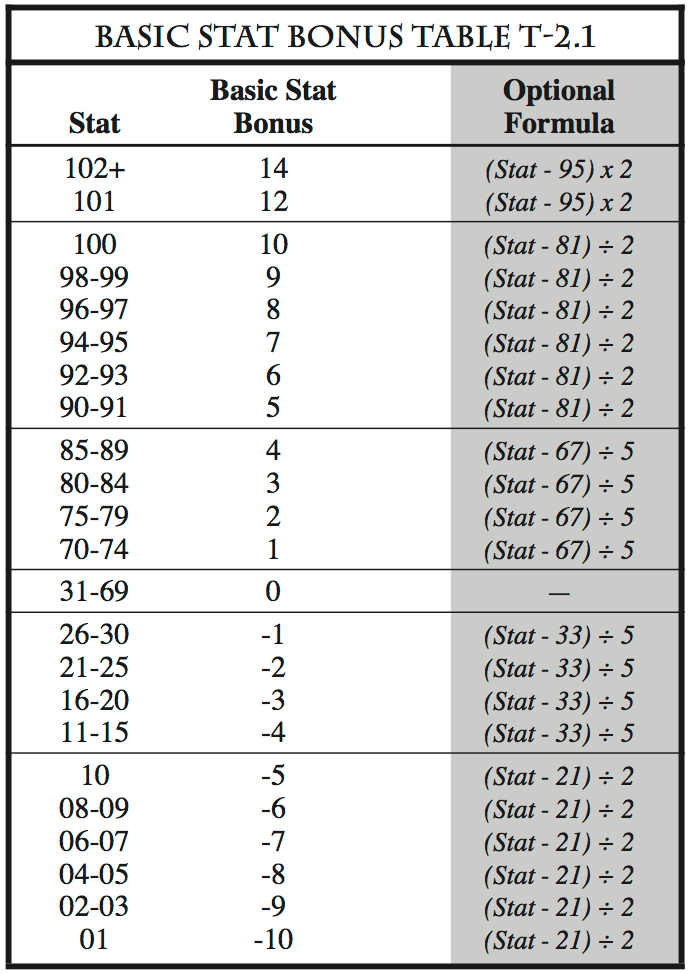

Stat bonuses are approximately one third of what they previously were. However, instead of averaging the stat bonuses applicable to a skill, you now just add the stat bonuses and three stat bonuses instead of two apply to most skills. This makes calculating the stat bonus for each skill much easier. Taking this new mechanism into account, stat bonuses are higher than before (e.g., +15 for a 90 stat and +30 for a 100 stat).

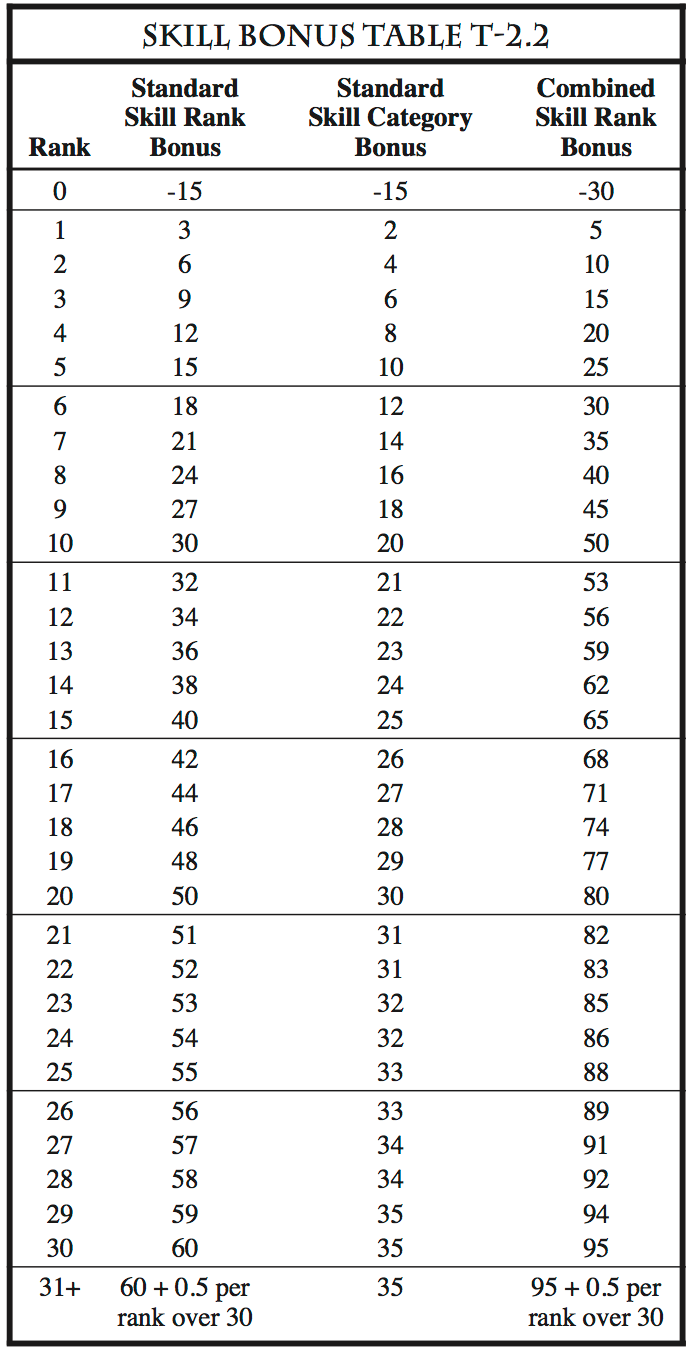

Skills — Most of the Companion skills have been incorporated and they have been totally reorganized into new groupings called skill categories. The total bonus for a skill is based upon its skill ranks and upon the rank of its skill category. Ranks in skills and skill categories must be developed separately, but a skill category rank affects all of the skills in that category (i.e., it is a “similar skill” mechanism).

The standard progression for a skill rank bonus is now: -15 if no ranks, +3 for ranks 1-10, +2 for ranks 11-20, +1 for ranks 21-30, and +0.5 for ranks over 30—the notation for this is “-15 • 3 • 2 • 1 • 0.5.” The standard progression for a skill category rank bonus is now: “-15 • 2 • 1 • 0.5 • 0.” So, if you develop one rank in a skill and one rank in its category each time you develop a skill, the combines progression is: “-30 • 5 • 3 • 1.5 • 0.5.” This is a bit more generous than the old progression of “-25 • 5 • 2 • 0.5 • 0.5” for skill ranks alone.

Some skill categories use a non-standard progression (e.g., Body Development, Power Point Development, Spell Lists, etc.). Skill categories with non-similar skills use a “Combined” progression of: “-30 • 5 • 3 • 1.5 • 0.5” for the skills and zero for all ranks of the skill category (i.e., development of the skill category gives no skill bonus). Certain skills can also be given lower (or higher) than normal DP costs by placing them in Occupation, Everyman, and Restricted skill categories—usually due to culture/ race, profession, or a factor of the individual GM’s world system.

Skill Development — With the new standard progression outlined above, you must develop two ranks (skill and skill category) to get the approximate skill rank bonus of the old system. To account for this, a character gets approximately twice the Development Points each level. In addition, since a skill category’s bonus applies to all skills in the category, developing multiple skills in the same category will effectively have a reduced DP cost.

There is no longer a DP cost of “#/*”—at most three ranks (#/#/#) can be developed in a skill (or skill category) each level. The ranks developed during adolescence skill development are now based upon the character’s culture/ race (i.e., DPs are not used).

DPs can now be used to develop Training Packages. A Training Package is a group of related ranks for skills and skill categories that can be developed at a reduced DP cost.

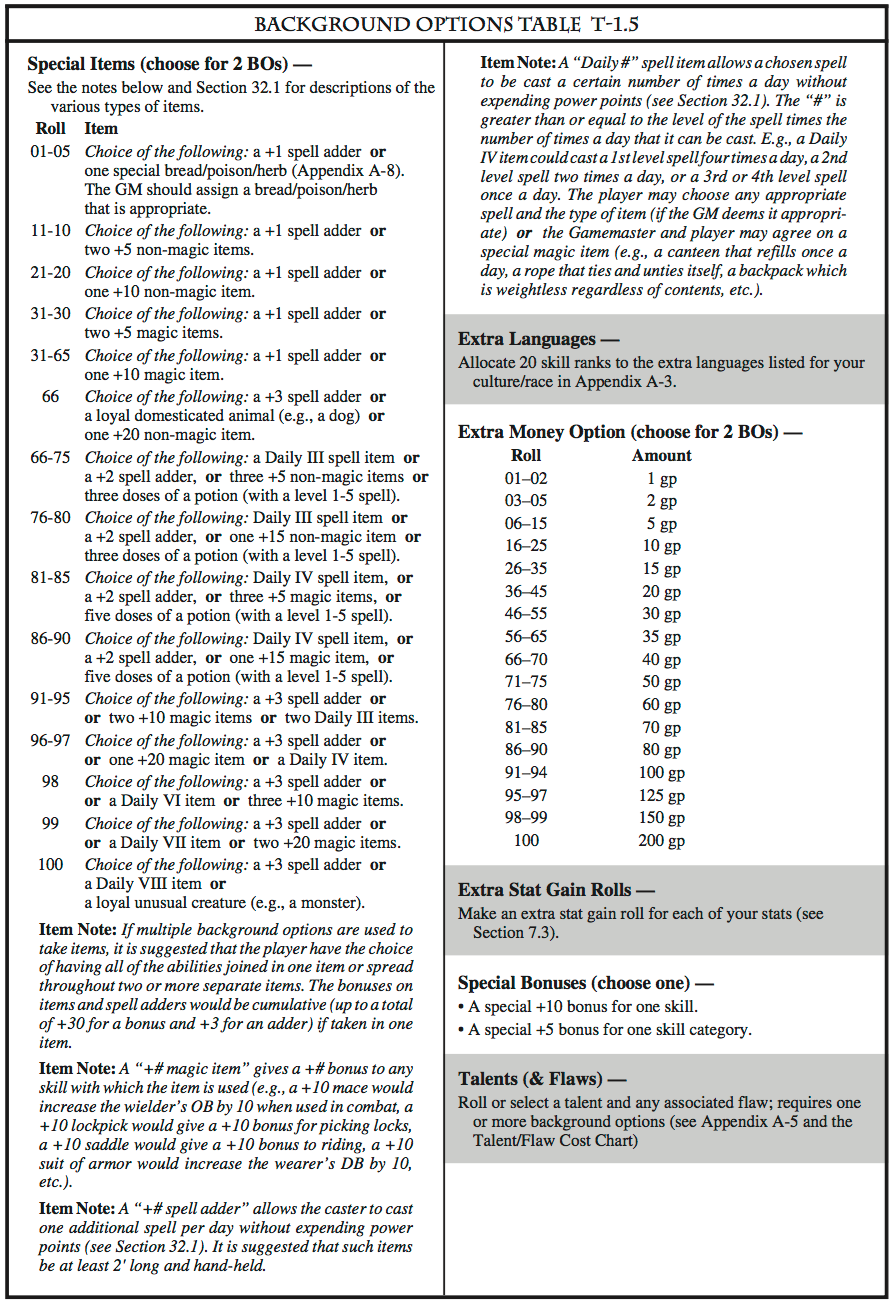

Spell List Development — Skill ranks are developed for each spell list—a spell is “learned” each time a rank is developed in its list. The DP cost for this varies based on the type of list (e.g., base, open, etc.), the number of the rank being developed, and how many different lists are developed in a given level advancement.

Background Options — A much wider variety of Background Options have been provided, including a balanced set of Talents and Flaws (see Appendix A-5).

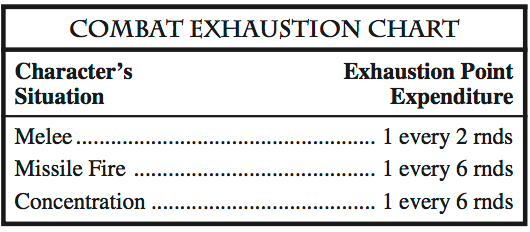

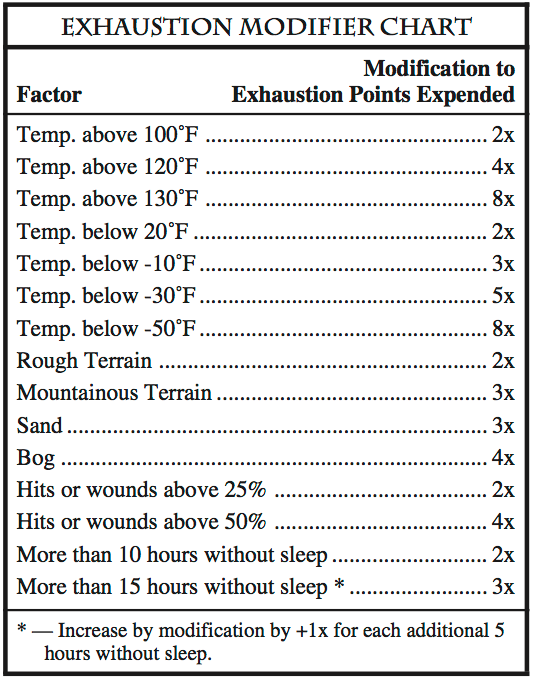

Recovery & Exhaustion — Recovery and exhaustion for Power Points, Hits, and Exhaustion Points are formalized and handled in a new way.

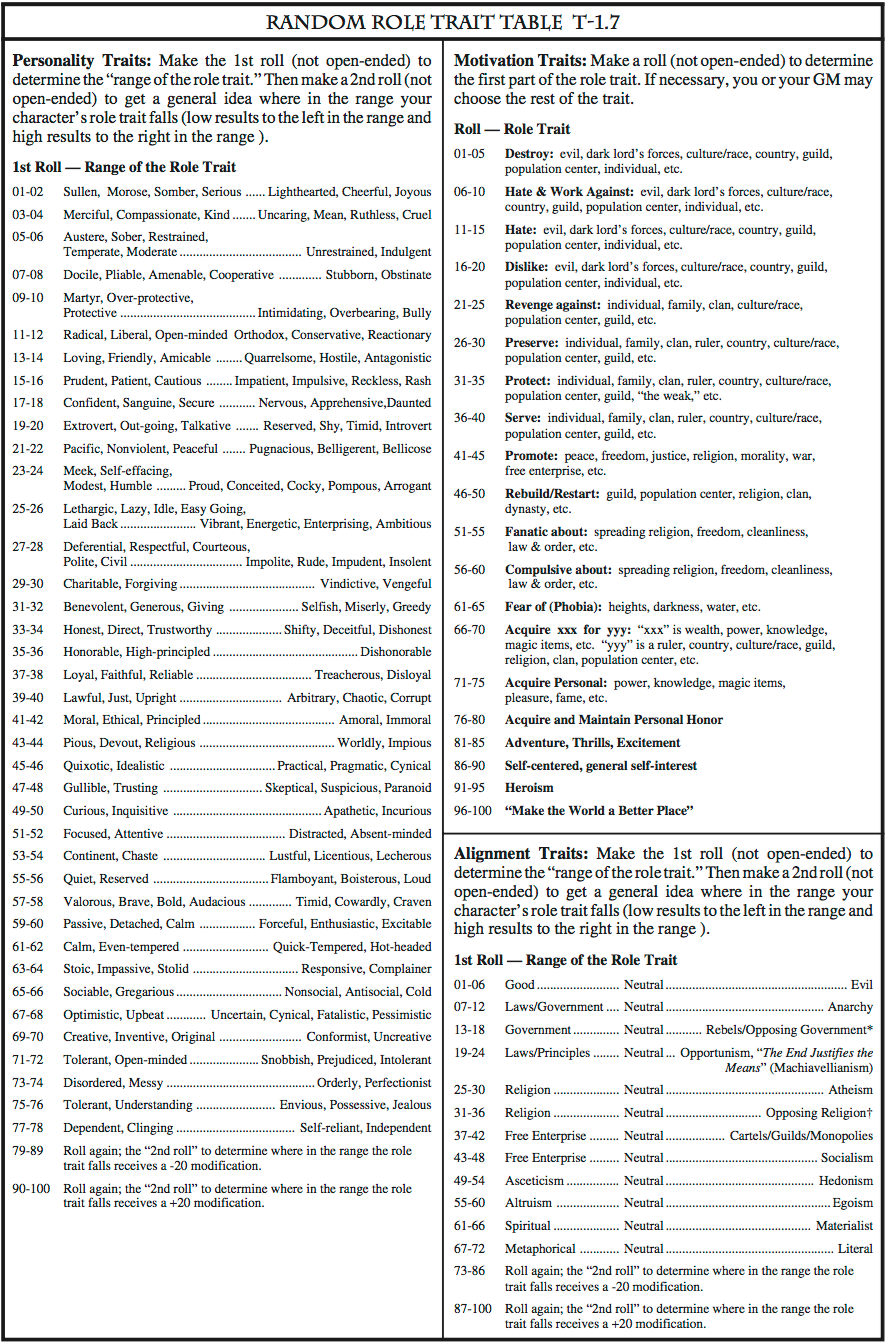

Role Traits — An system of “role traits” is provided to help you develop your character’s motivation, personality, alignment, and physical appearance.

Performing Actions — The entire turn sequence has been redone to provide for a more fluid resolution of actions and activities. Each character may take up to three “actions” a round. A general decision on how fast to attempt to accomplish an action must be made: as a snap action (very fast, with a -20 modification ), as a normal action, or as a deliberate action (slow, but with a +10 modification). Within each of these types, actions are resolved based upon each character’s Initiative Roll (2d10+Qu bonus+mods).

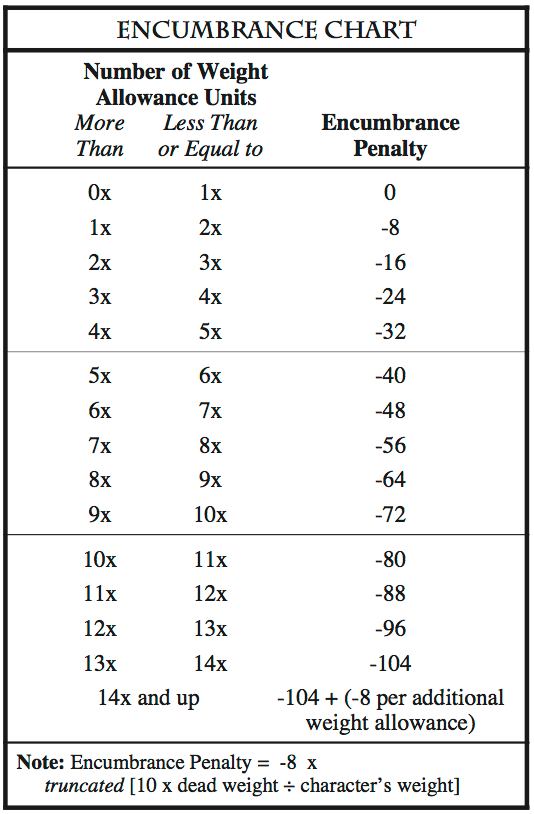

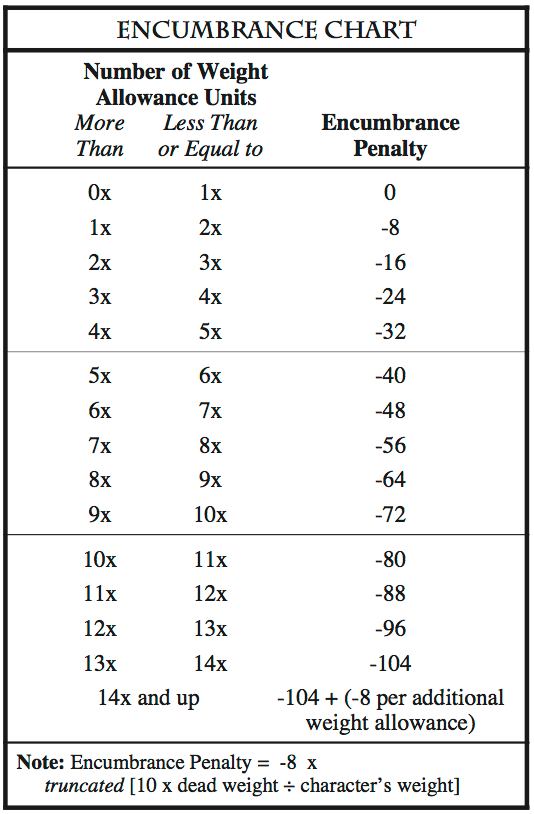

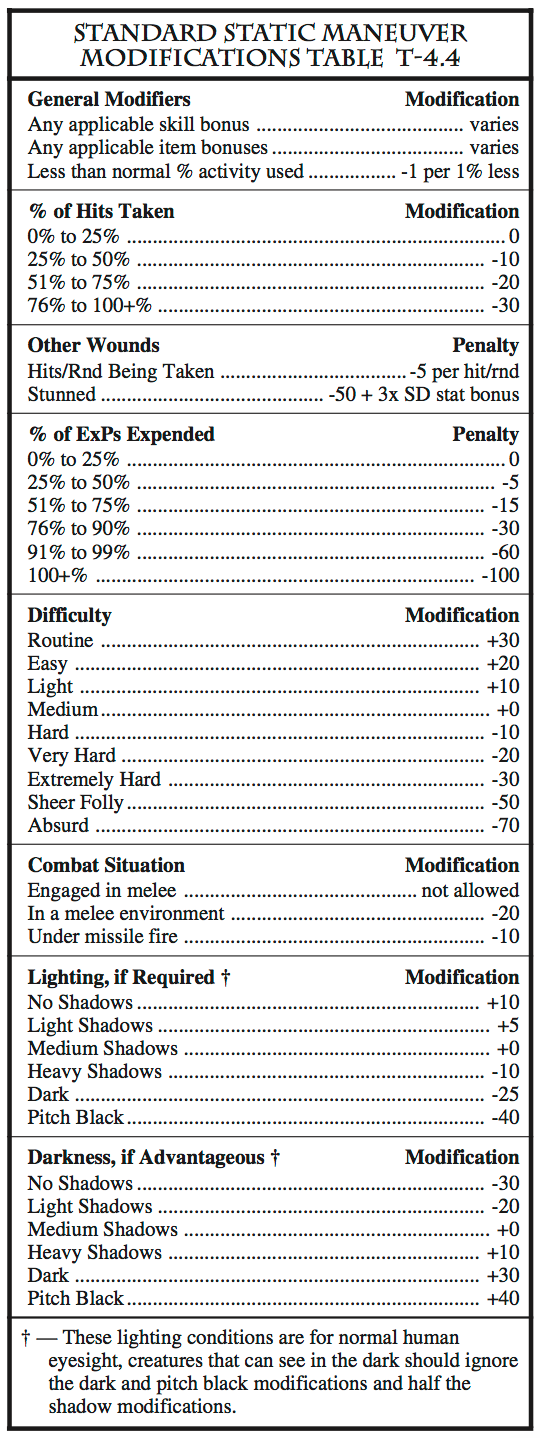

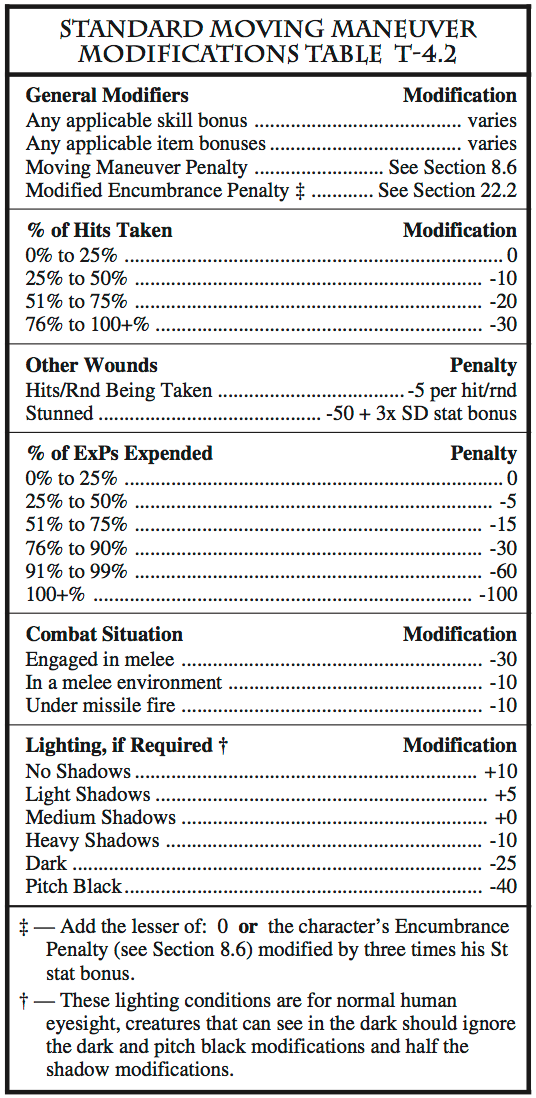

In addition, the resolution of attacks has been generalized, combining all of the old attack resolution rules from Arms Law, Spell Law, and Character Law. The static maneuver tables have been expanded and standardized. The movement and encumbrance rules have been finetuned.

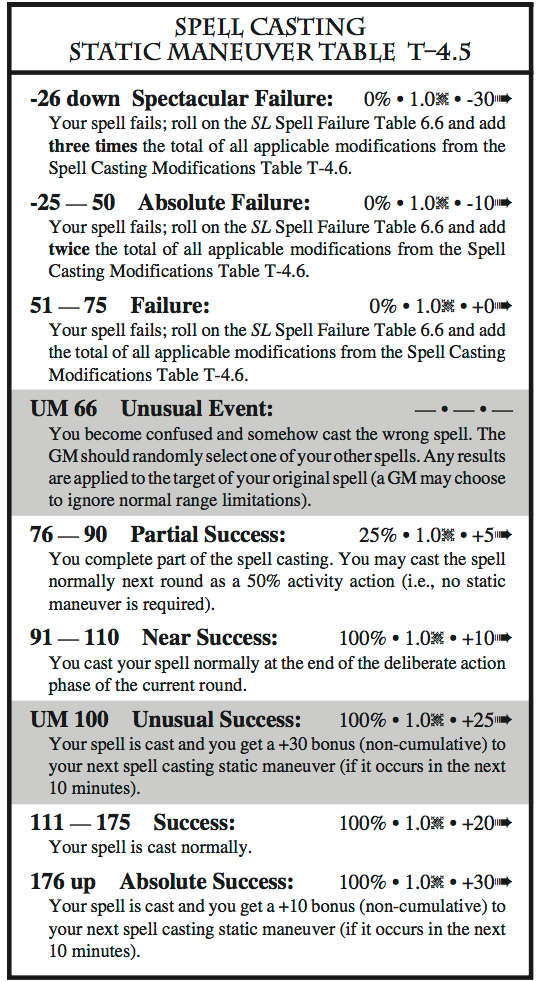

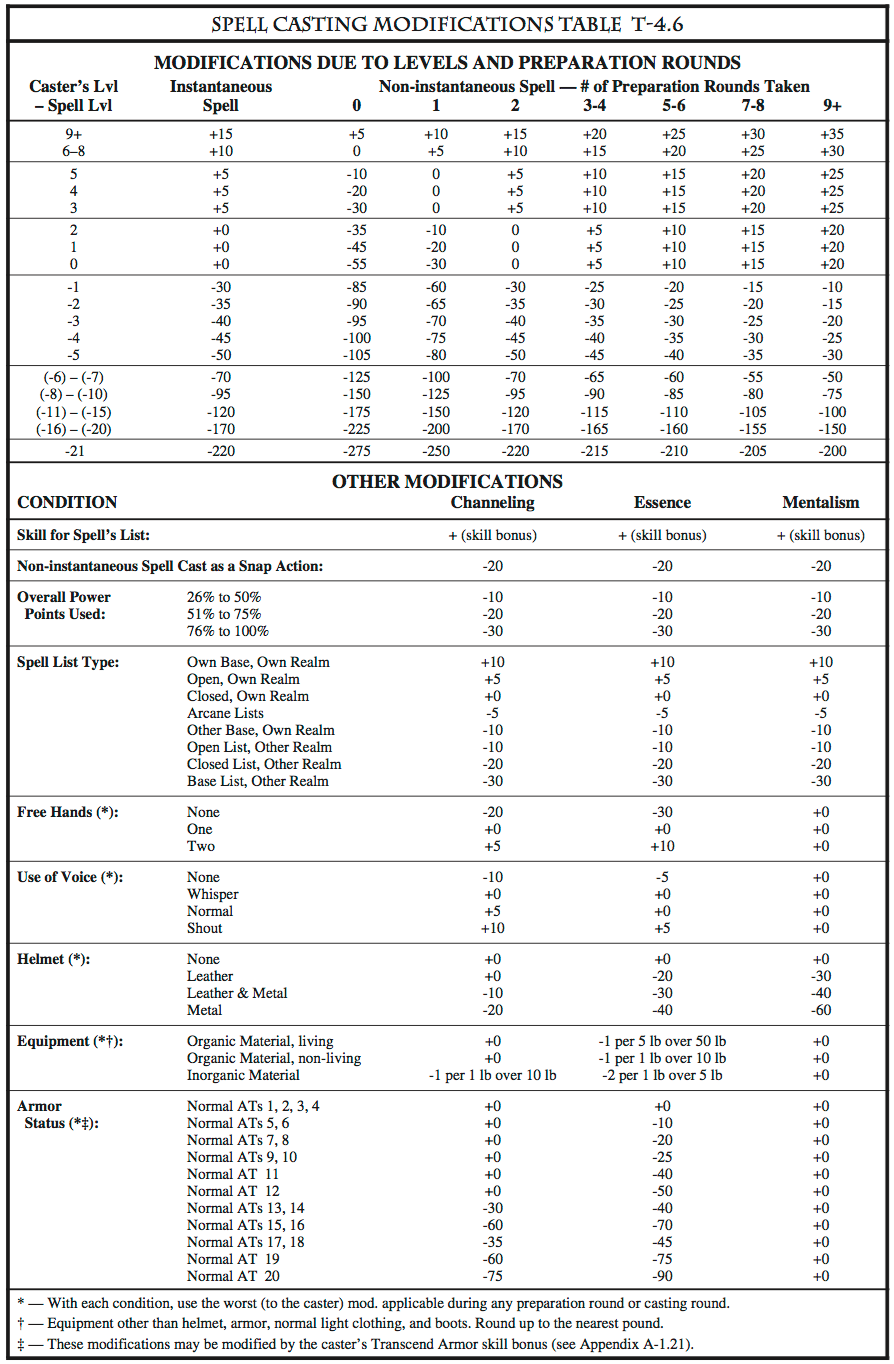

Finally, the old Extraordinary Spell Failure rules have been redone and incorporated into a spell casting static maneuver that is required for all spell casting that does not meet the “automatic spell casting” requirements.

This section provides some brief descriptions of the existing and planned products in ICE’s Rolemaster line. These products fall into two categories: core products (Arms Law, Spell Law, Gamemaster Law, and the Rolemaster Standard Rules) and non-core products.

The RM core products are the four products that make up the Rolemaster Standard System: Arms Law, Spell Law, Gamemaster Law, and the Rolemaster Standard Rules.

Rolemaster Standard Rules (RMSR) — This product provides all the guidelines and rules needed to play Rolemaster. Its primary parts are concerned with character definition, character design, performing actions, and outlining the Gamemaster’s tasks. Details of the RMSR are not covered here because it is the product you are currently reading. See Section 1.1.1 for some key features of the RMSR.

Arms Law (AL) — This product is a detailed fantasy/ medieval combat system covering the mechanics of weapon attacks, animal attacks, martial arts attacks, fumbles, and critical strikes. It has been designed to provide a logical, detailed, manageable procedure for resolving combat between individuals and small groups.

This combat system provides 29 weapon attack tables, each of which integrates the strengths and weaknesses of one specific weapon versus 20 different armor types. Additional guidelines are given for dozens of other weapons. AL also provides animal attack tables and martial arts attack tables which handle all kinds of unarmed attacks. To handle specific, detailed occurrences during combat, AL includes two fumble tables and a dozen different critical strike tables. See Section 1.1.2 for some other key features of AL.

Spell Law (SL) — This product deals with the integration of spells and magic into a fantasy role playing environment. Real skill in play is emphasized, since the choice of a spell and its application to a given situation become the key elements of success. To this end, SL describes over 2,000 spells, organized into three “realms of power” and keyed to 15 different professions.

The spells in SL are organized into “spell lists”, each of which consists of spells which are related in function or base application. Spell lists are grouped into categories based upon professions and realms of power (Channeling, Essence, and Mentalism). See Section 1.1.3 for some other key features of SL.

Gamemaster Law (GML) — This product is an aid for those who wish to create and employ an alternate world setting for their fantasy role playing game. It is designed to give Gamemasters an idea of the essential elements of a fantasy realm, and provides ways to develop a rich, consistent foundation upon which to build as their campaign progresses. See Section 1.1.4 for some other key features of GML.

The non-core Rolemaster products fall into four broad categories: secondary “Law” products, source products, companion products, and other products.

These products are specific topic Rolemaster rules books. Some potential topics/titles include:

War Law — The original RM mass combat system is still usable with the RMSS. It will eventually be reworked to more closely mesh with the RMSS and to make “unit generation” more workable.

Sea Law — The original RM ship combat system is still usable with the RMSS.

Equipment Law — A compilation of adventuring equipment and a system for defining and integrating various technology levels into a RM game.

Talent Law — A point cost based system formalizing and detailing talents, powers, and flaws available through background options.

These products provide specific topic RM source material and play aids. Some potential topics/titles include:

Creatures & Monsters — ICE’s compendium of information and statistics for two key elements of fantasy role playing: creatures, and encounters. It also includes guidelines and statistics for dozens of new races.

Rolemaster GM Screen — A GM screen with a summary booklet of some of the most commonly accessed tables and charts.

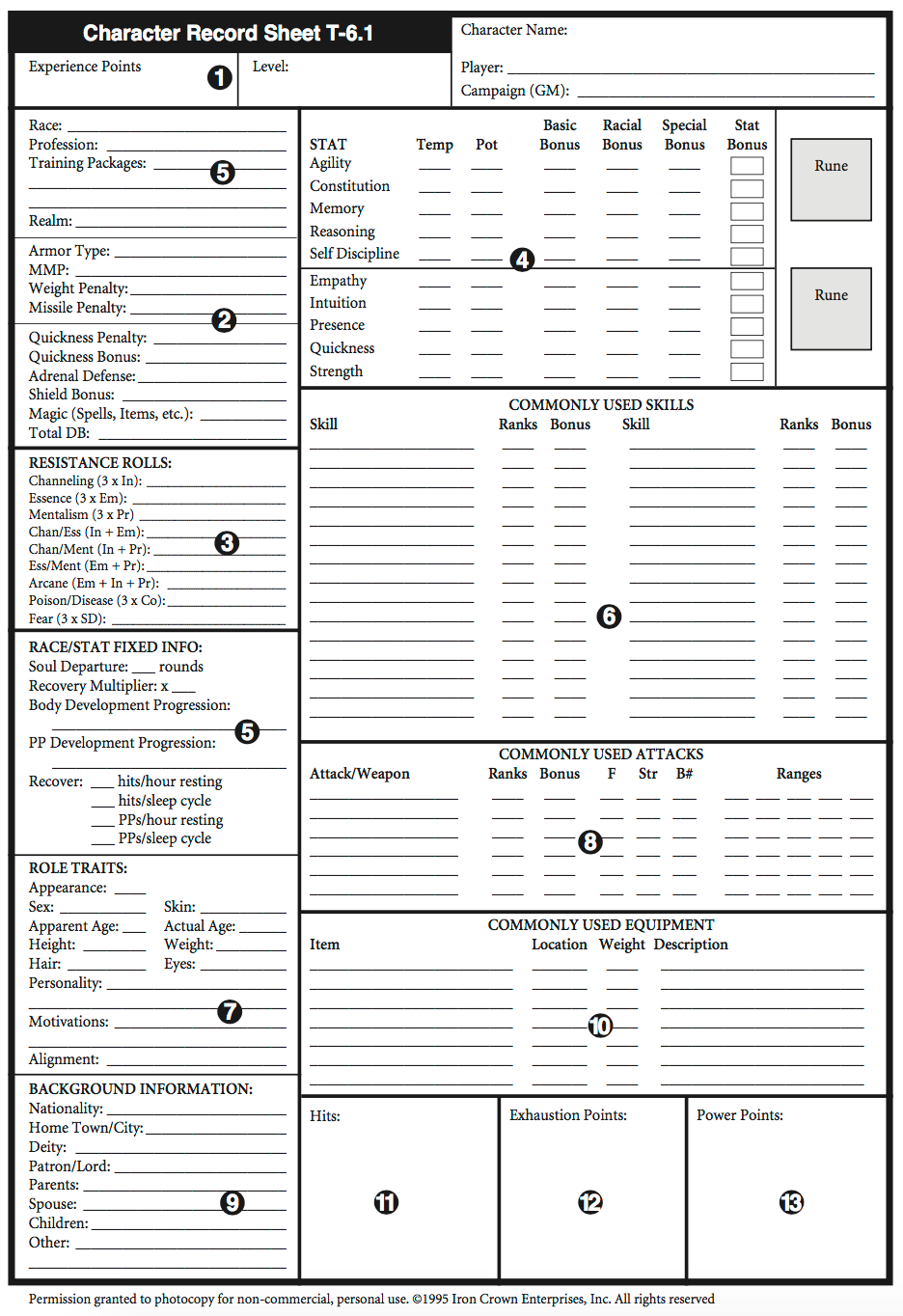

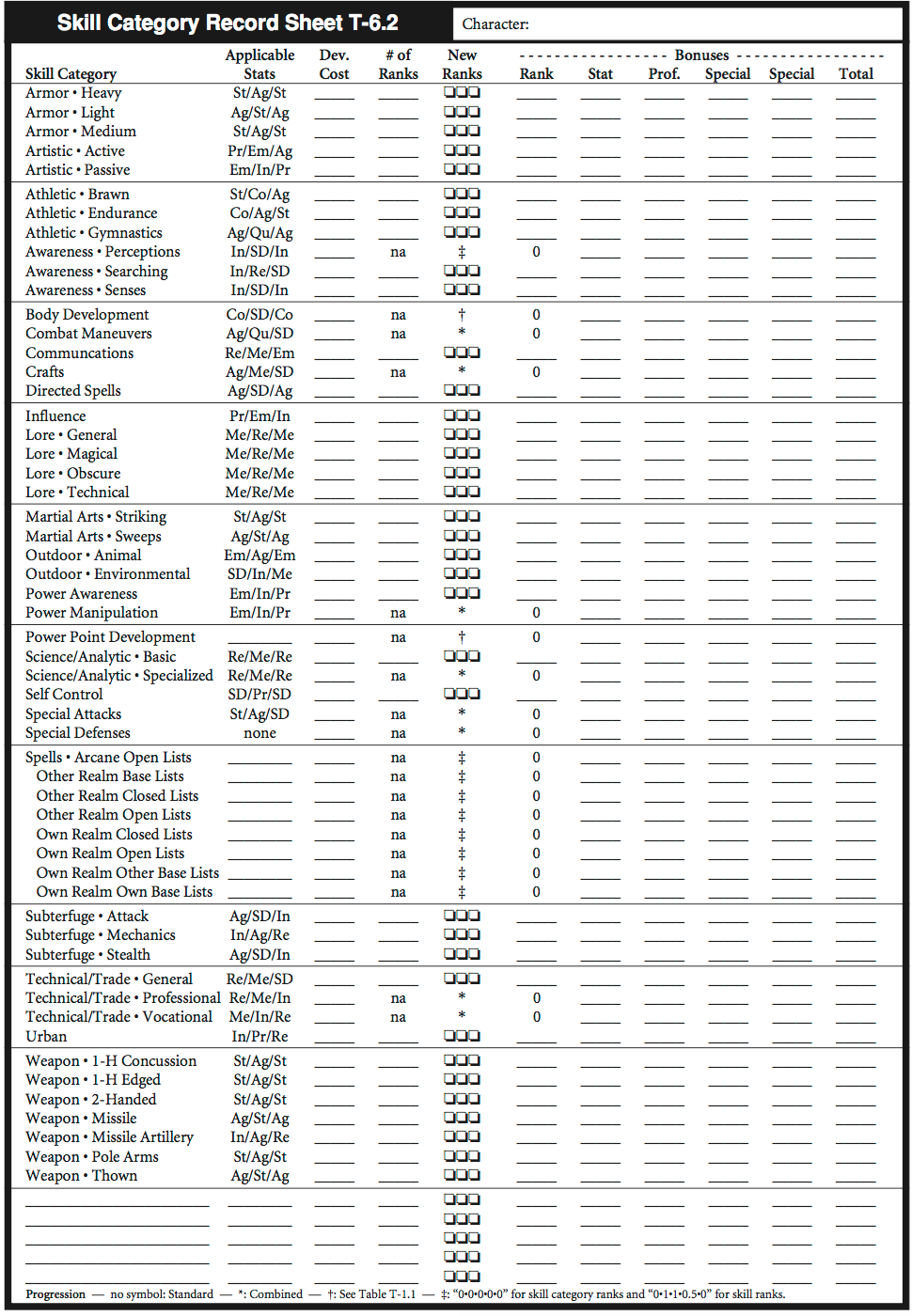

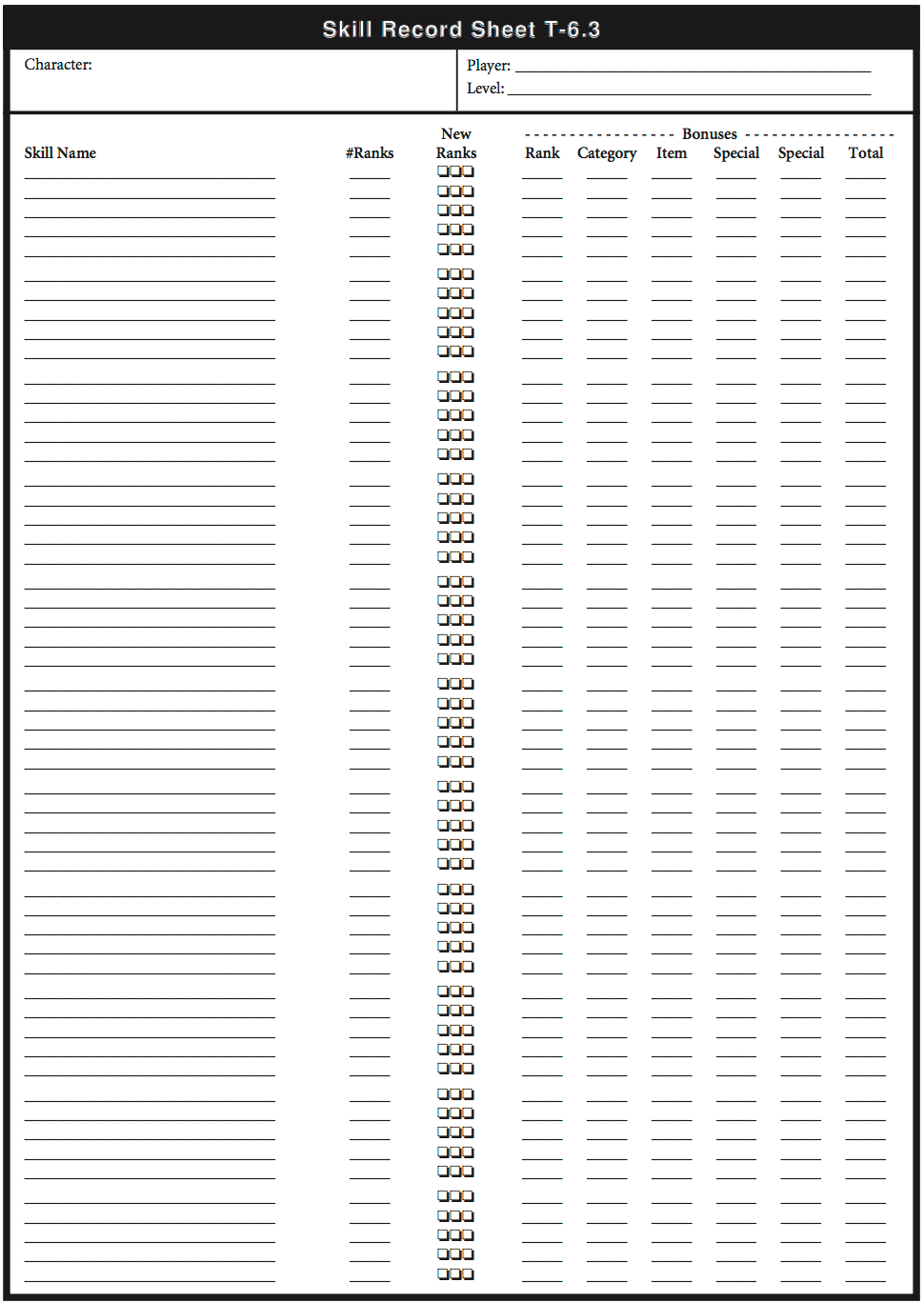

Rolemaster Character Sheets — Contains character sheets individualized for the various professions.

Races & Cultures — An expanded compendium of information and statistics for RM races and cultures.

Treasures & Riches — An expanded collection of magic items and treasures.

Heroes & Rogues — Fully developed RM characters for use as PCs and NPCs.

Weapons & Armor — A compendium of various types of weapons and armor for RM.

These products provide RM optional rules and variants on a focused topic. Some potential topics/titles include:

| Arcane Companion | Essence Companion |

| Channeling Companion | Mentalism Companion |

| Arms Companion | Stealth Companion |

| Martial Arts Companion |

The Shadow World™ Series — Modules and adventures in a rich, self-contained fantasy environment designed specifically for use with for RM, but which can be used as isolated or hidden areas in any GM’s campaign world.

Space Master™ — ICE’s science fiction role playing system is compatible with RM, allowing Gamemasters to inject sci-fi elements into their FRP games and vice versa.

Middle-earth Role Playing™ — A complete system specifically designed to introduce people to fantasy role playing in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth. It is suitable for those who have never before played a FRP game, as well as more experienced gamers who are looking for a realistic, easy to play FRP system for low-level adventures. It is compatible with Rolemaster and can serve as a great introduction to RM for novices.

ICE’s Middle-earth® Support Products — A wide variety of rules, guidelines, and modules for use with fantasy role playing in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth. Completely compatible with both RM and Middle-earth Role Playing.

Each die used in Rolemaster is either a 10-sided or a 20-sided dice which gives a result between 0 and 9. If two of these dice are used, a variety of results can be obtained. However, results between 1 and 100 are the primary basis of the RMSS (i.e., RM is a “percentile” system).

Note: These dice can be obtained at your local hobby and game stores.

1-100 Roll (1d100) — Most of the rolls in Rolemaster are “1-100” rolls (also called “d100” rolls). To obtain a 1-100 result roll two dice together—one die is treated as the “ten’s” die and the other as the “one’s” die (designate before rolling, please). Thus a random result between 01 and 100 (a “00” is treated as 100) is obtained.

Example: The GM asks a player to make a 1-100 roll. The two dice are rolled; the ten’s die is a “4” and the one’s die is a “7.” Thus the result is “47.”

Low Open-ended Roll — To obtain a “low open-ended roll” first make a 1-100 roll. A roll of 01-05 indicates a particularly unfortunate occurrence for the roller. The dice are rolled again and the result is subtracted from the first roll. If the second roll is 96-00, then a third roll is made and subtracted, and so on until a non 96-00 roll is made. The total sum of these rolls is the result of the low open-ended roll.

Example: The GM asks a player to make a low open-ended roll, and the initial roll is a 04 (i.e., between 01 and 05). A second roll is made with a result of 97 (i.e., between 01 and 05); so a third roll is made, resulting in a 03. Thus, the result of the low open-ended roll that the GM requested is -96 (= 04 - 97 - 03).

High Open-ended Roll — To obtain a “high open-ended roll” first make a 1-100 roll. A roll of 96-00 indicates a particularly fortunate occurrence for the roller. The dice are rolled again and the result is added to the first roll. If the second roll is 96-00, then a third roll is made and added, and so on until a non 96-00 roll is made. The total sum of these rolls is the result of the high open-ended roll.

Example: The GM asks a player to make a high open-ended roll, and the initial roll is a 99 (i.e., between 96 and 100). A second roll is made with a result of 96; so a third roll is made with a result 04. Thus, the result of the high open-ended roll that the GM requested is 199 (= 99 + 96 + 04).

Open-ended Roll — An open-ended roll is both high open-ended and low open-ended.

1-10 Roll (1d10) — In instances when a result (roll) between 1 and 10 is required, only one die is rolled. This gives a result between 0 and 9, but the 0 is treated as a 10. Such a roll is referred to as “1-10” or “d10.”

1-5 Roll (1d5) — Roll one die, divide by 2 and round up (“d5”).

1-8 Roll (1d8) — Roll one die; if the result is 9 or 10, reroll until a 1 to 8 result occurs (“d8”).

5-50 Roll (5d10) — Roll 1-10 five times and sum the results.

2-10 Roll (2d5) — Roll two dice, divide each result by 2 (round up), and then add the two results to obtain the “2- 10” (“2d5”) result.

Other Required Rolls — Any other required rolls are variants of the above.

Certain results on some rolls indicate an immediate effect—no modifications (or bonuses) are considered. These rolls are marked on the appropriate charts with a UM. For example, all weapon attacks result in a fumble if the initial unmodified 1d100 roll falls within the fumble range of the weapon.

When making calculations and using the formulae in the RMSS, the results often do not come out evenly.

You should maintain fractions until you come up with a final result that will be used in play.

But, whenever a final result has a fractional remainder, it is always rounded up to the nearest whole number (i.e., fractions less than 0.5 goes 0, and greater than or equal to 0.5 goes to 1).

Example: Darien has development stats of 46, 57, 73, 91, and 99. His available development points are equal to: (46+57+73+91+99)÷5 = 366 ÷ 5 = 73.2. This rounds up to 73 DPs. If the stats were 46, 60, 73, 91, and 99, the DPs would be: (46+60+73+91+99)÷5 = 369 ÷ 5 = 73.8. This rounds up to 74 DPs.

Example: Darien has 25 skill category ranks in Power Awareness, his skill category rank bonus is equal to: (10x2)+(10x1)+5x(0.5) = 20+10+2.5 = 32.5. This rounds up to 33.

The majority of unique terms found in the RMSS are not described below; rather they are usually described when they are used in the text. The terms defined below are frequently used or are very important for using and understanding the RMSS.

Action: An action is one of the activities which a character may perform during a round (10 seconds).

Animal: A living creature capable of feeling and voluntary motion, but excluding those characterized as beings.

Area Attack Spell: An elemental attack spell that attacks an area rather than a specific target; e.g., Cold Ball, Fire Ball, etc.

Attack Roll: A “Roll” that is used to determine the results of a melee or missile attack.

Basic Attack Spell: A spell that attacks a target, but which is not an elemental attack spell.

Base Spell List: A spell list that is easily learnable only by members of one specific profession.

Being: Any intelligent creature, including all humanoid types, enchanted creatures, etc. Intelligence should be characterized by system and/or Gamemaster.

Campaign: An ongoing fantasy role playing game which takes place as a series of connected adventures, with respect to both time and circumstance.

Chance: Often an action or activity has a “chance” of succeeding or occurring, and this chance is usually given in the form of # %. This means that if a roll (1-100) is made (see below) and the result is less than #, then the action or activity succeeds (or occurs); otherwise it fails. Alternatively, you can roll (1-100) and add the result to the #; if the result is greater than 100, then the action or activity succeeds (or occurs); otherwise it fails.

Channeling: One of the realms which provide the source of power for spells (see Section 4.1).

Closed Spell List: A spell list that is easily learnable only by the Pure and Hybrid spell users of the spell list’s realm.

Combat Roll: See “Attack Roll.”

Concussion Hits: See “Hits.”

Critical Strike: Unusual damage due to a particularly effective attack. Note: The term “critical” (or just crit) will often be used instead of “critical strike.”

Defensive Bonus (DB): The total subtraction from a combat roll due to the defender’s advantages, including bonuses for the defender’s quickness, shield, armor, position, and magic items (see Section 23.2).

Dice Roll: See Roll.

Directed Attack Spell: An elemental attack spell that attacks a specific target; e.g., Ice Bolt, Fire Bolt, etc.

Downed: When a combatant falls to the ground, he is considered downed. This does not mean prone. It is presumed that the combatant is still moving.

Elemental Attack Spell: An spell which creates and uses fire, cold, water, ice, or electricity to attack a target. The “elements” created by these spells are real when the spell is cast.

Essence: One of the realms which provide the source of power for spells (see Section 4.2).

Experience Level (Level): A character’s level is a measure of his current stage of skill development, and usually is representative of his capabilities and power.

Failure: See “Spell Failure.”

Fire: To make a missile attack (verb), or a number of missile attacks (noun).

Fumble: An especially ineffective attack which yields a result that is disadvantageous for the attacker.

Gamemaster (GM): The gamesmaster, judge, referee, dungeonmaster, etc. The person responsible for giving life to a FRP game by creating the setting, world events and other key ingredients. He interprets situations and rules, controls non player characters, and resolves conflicts.

Group: A collection of player characters.

Herbs: A plant or plant part valued for medicinal qualities. Hits (Concussion Hits): Accumulated damage, pain, and bleeding, that can lead to shock, unconsciousness, and sometimes death (also called Concussion Hits). Each character can take a certain number of hits before passing out (determined by his “Body Development” skill).

Hybrid Spell User: A spell user who can easily learn spells in two different realms.

Inanimate: Not having qualities associated with active, living, organisms; not animate.

Initiative: The factor that helps determine the order in which combatants resolve their attacks; e.g., the combatant with the highest initiative attacks first.

Inorganic: Involving neither organic life or products of organic life.

Level: See “Experience Level.”

Lord Spell: A spell is keyed to a 20th level effect and will normally be defined in multiples/increments of 20.

Maneuver Roll: A roll that is used to determine the results of a maneuver.

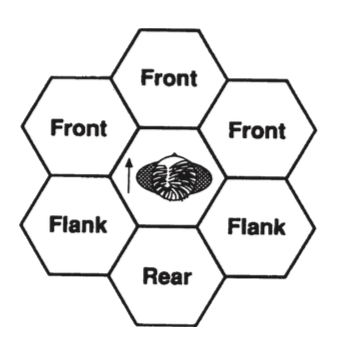

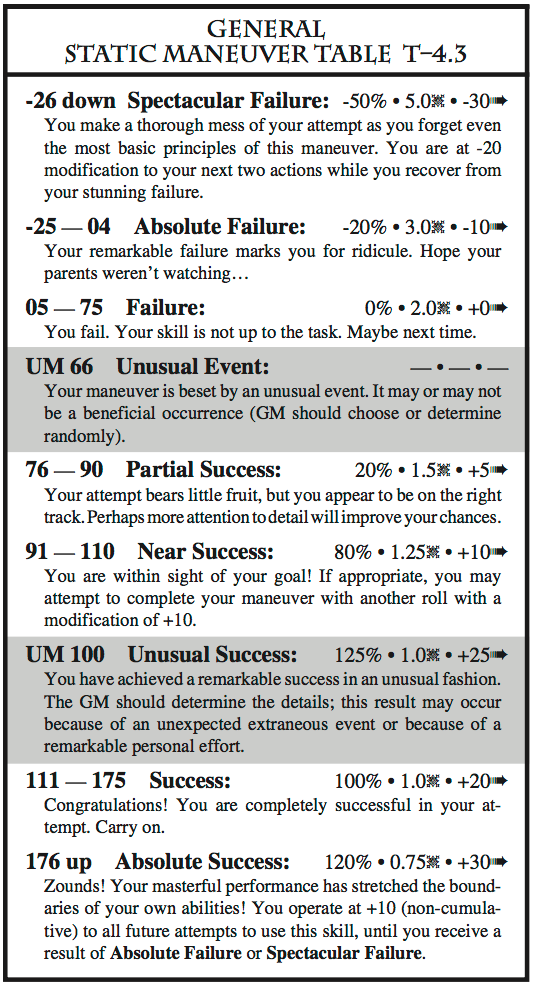

Maneuver: An action performed by a character that requires unusual concentration, concentration under pressure, or a risk (e.g., climbing a rope, balancing on a ledge, picking a lock, etc.). Maneuvers requiring movement are “Moving Maneuvers” (MM), and other maneuvers are called “Static Maneuvers” (SM).

Martial Arts (MA): Forms of attack and self-defense which involve specialized mental and physical training and coordination. Most unarmed combat fall into this category.

Mass Spell: A spell with its “# of targets” or its “area of effect” based upon the caster’s level.

Melee: Hand-to-hand combat (i.e., combat not using projectiles, spells, or missiles) where opponents are physically engaged— be it a fist fight, a duel with rapiers, or a wrestling match.

Mentalism: One of the realms which provide the source of power for spells (see Section 4.3).

Missile weapon: In the RMSS, this indicates a low velocity airborne projectile, usually from a manually fired weapon. Such weapons include an arrow from a bow, a quarrel from a crossbow, a stone from a sling, etc. Thrown weapons are also included in this area. Normally, missile weapons do not include projectiles fired by explosions or other high-velocity propulsion means (e.g., guns are “projectile weapons”).

Non Attack Spell: A spell which does not attack a target.

Non Spell User: A character with very little spell casting capability, but with a great deal of capability in non-spell areas.

Non-Player Character (NPC): A being in a fantasy role playing game shows actions are not controlled by a player, but instead are controlled by the Gamemaster.

Offensive Bonus (OB): Each character has an “offensive bonus” when he is making an attack—this OB can include bonuses for the character’s stats, superior weapon, skill rank, magic items, etc. This OB is added to any attack rolls that are made when he is using that particular attack (see Section 23.3).

Open Spell List: A spell list that is easily learnable by any profession of the spell list’s realm.

Organic: Of or deriving from living organisms.

Orientation Roll: A roll representing a character’s degree of control following an unusual action or surprise.

Parry: The use of part of a character’s offensive capability to effect an opponent’s attack.

Player Character (PC): A character whose actions and activities are controlled by a player (as opposed to the Gamemaster). Player: A participant in a fantasy role playing game who controls one character, his player character.

Power Point Multiplier (PP Multiplier): An item that increases the wielder’s inherent power points (see Section 32.1).

Power Points (PP): A number which indicates how many spells a character may intrinsically cast each day (i.e., between periods of rest). In order to cast a spell, the caster must expend a number of “power points” equal to the level of that spell.

Profession: A character’s profession is a reflection of his training and thought patterns; in game terms, it affects how much effort is required to develop skill in various areas of expertise.

Projectile weapon: As opposed to a missile weapon, this indicates a device which mechanically fires a high-velocity projectile (e.g., a gun).

Prone: When a combatant stops moving (and usually drops to the ground), he is considered prone.

Pure Spell User: A spell user who can easily learn spells in only one of the three realms. Most spell using professions fall into this category.

Realm: All spells and the power required to cast spells are classified in the three “realms” of power: Essence, Channeling, and Mentalism (see Section 4.0).

Resistance Roll (RR): A dice roll which determines whether or not a character successfully resists the effect of a spell, poison, disease, or some other form of adversity.

Roll: Two different colored 10-sided dice are used to resolve any activity requiring a “Roll;” such dice are available in most hobby and toy stores. Each of these dice has two sets of the numbers: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, and 9. These dice can be used to obtain a variety of results. These various results are described in Section 1.1.4.

Round: The time (10 seconds) required to perform one action.

Self-reloading: Refers to any weapon which reloads (or recharges) itself and is ready for another shot almost immediately (i.e., it is capable of two attacks in the same round). Most projectile weapons fall into this category, while normal bows and thrown weapons do not. Normally self-reloading weapons only occur in FRP games in the form of magic items.

Semi Spell User: A spell user with some spell casting capability in one realm, but also with considerable non-spell capabilities. A character is a Semi spell user by virtue of his profession only. Non spell users who somehow learn spells are still termed Non spell users.

Session: A single sitting of game adventure. A number of sessions form a campaign.

Shot: A missile attack.

Skill: Training in an area which influences how effectively a character is able to perform a particular action or activity. “Skill Rank” is a measure of the effectiveness of a specific skill (see Section 6.0 and Appendix A-1).

Skill Category: A grouping of related skills that require the same approximate effort to develop. “Skill Category Rank” is a partial measure of the effectiveness of the specific skills in that category (see Section 6.0).

Slaying item or weapon: An item or weapon specifically designed to combat and/or destroy a being or type of being (e.g., a Dragon-slaying sword or staff).

Spell Adder: An item that allows its wielder to cast a set number of spells without expending power points (see Section 32.1).

Spell Failure: This occurs when a particularly low roll is made when casting a spell; it indicates possible malfunction or backfiring of the spell.

Spell Level: The minimum skill rank for the spell’s list that is necessary for a spell user to know or inherently cast that particular spell.

Spell List: A grouping and ordering of related spells based upon a correlation of level, intricacy, and potency of the spells. A character who has developed (i.e., “learned”) a spell list to a specific skill rank is able to cast a spell from that list if its level is less than or equal to that skill rank.

Spell points: The same as the term Power Points.

Stat (Characteristic): One of 10 physical and mental attributes which are considered most important to an adventurer in a FRP game. Stats affect how well a character develops his skills, moves, fights, takes damage, absorbs information, etc. Stats in the RMSS are gauged on a scale from 1-100. To convert from a 3-18, simply multiply be 5 and add 5.

Stat Bonus: Each stat is assigned a bonus that is used to modify skill checks.

Static Maneuver (SM, Static Action): An action performed by a character which requires unusual concentration or thought under pressure and does not involve pronounced physical movement.

Swing: A melee attack (noun), or to make a melee attack (verb).

Target: The term “target(s)” refers to the being(s), animal(s), object(s), and/or material that a melee attack, missile attack, or spell attempts to affect.

True Spell: A “True” spell is the highest level version of a specific spell type. Its potency will define the upper limit of the effect(s) derived from a given spell.

Wound: An injury in which the skin is torn, pierced, or cut.

The Rolemaster Standard System (RMSS) has four separately indexed sets of “core” rules:

| Product | Referencing Prefix | |

| Rolemaster Standard Rules (RMSS) | none | |

| Arms Law | AL | |

| Spell Law | SL | |

| Gamemaster Law | GML | |

In general, a specific rules “section” in the RMSS is referenced by using the abbreviation for the appropriate set of rules (no prefix for the product you are currently reading, the word “Section,” and the appropriate section number (or numbers or range of numbers).

Example: This text is in “Section 2.0.” The introductory material in Arms Law is in “AL Section 1.0.” The introductory material in Spell Law is in “SL Section 1.0.” The introductory material in Gamemaster Law is in “GML Section 1.0.”

Note: Other, non-core products will refer to the sections in this product (i.e., the Rolemaster Standard Rules) with a “RMSR” prefix.

The Gamemaster should first skim the rules to get an overall view of the system. Then he should read all of the rules in the RMSR, AL, SL, and GML thoroughly. If a section is not understood immediately, it should be marked and referred to again after all of the rules have been read. Examples are included to aid in absorbing the rules. The Gamemaster need not memorize or fully analyze the significance of all of the rules at first. The rules are organized in such a fashion that many situations can be handled by referring to specific rules sections when they first arise.

The Gamemaster should also read the optional rules (Appendix A-9) and decide which he feels are appropriate for his game and world system. He should make sure that the players are clear as to which are to be used and which are not to be used.

The players should first read Sections 1.1-1.3 to get an overview of the component parts of the RMSS. Next, they should skim Part II (Sections 3.0-10.0) to get an idea of the major factors affecting a character. Then they should generate a character by following the procedure and examples outlined in detail in Part III (Sections 11.0-17.0), referring to Part II for explanations of the various aspects of a character.

Before play begins, the players should also read (or have explained to them) Part IV (Sections 18.0-25.0) so that they will understand what their options are in a tactical (usually combat) situation. In addition, players whose characters are spell users should read Section 26.0 in order to obtain an understanding of the spell casting process. It is not absolutely necessary for the players to immediately read the rest of the RMSS material, since much of that material is concerned with how the Gamemaster can handle the setting of the game, the plot elements, and other factors. However, a complete reading of the system will enable the players to understand the mechanisms which govern play.

When a player has made his initial choices for his character, he should get a copy of the page for his character’ s culture or race (Appendix A-3) and the page for his profession (Appendix A-4). Most of the information necessary for creating his specific character will be summarized on these two pages.

In a fantasy role playing game, each of the “players” controls the actions of his “player character,” while the Gamemaster controls the actions of all of the other characters (called non-player characters). Thus, one of the main objectives of a FRP game is for you to take on the persona of your player character, reacting to situations as your character would. This is the biggest difference between FRP games and other games such as chess or bridge. Your player character is not just a piece or a card. In a good FRP game you place yourself in your character’s “role.”

A role playing game deals with adventure, magic, action, danger, combat, treasure, heroes, villains, life, and death. So, by taking on the role of your characters, you can leave the real world behind for a while, and enter a world where the fantastic is real and reality is limited only by your imagination and that of the other players and the Gamemaster.

Your character will have certain factors that define his attributes, capabilities, and skills. These factors determine how much of a chance your character has of accomplishing certain actions. Many of the actions that your character will attempt during play have a chance of success and a chance of failure. Therefore, even though actions are initiated by the Gamemaster and the players during the game, the success or failure of these actions is determined by the Rolemaster rules, the factors that define your character and the random factor of a roll of the dice.

The specific factors that define your character are presented and discussed in the rest of Part II (Sections 3.0–10.0). Part III (Sections 11.0-17.0) presents the actual character design process, while Part IV (Sections 18.0-26.0) presents the guidelines for performing actions.

Cultural and racial characteristics for a fantasy role playing game are heavily dependent upon the world system being used by the Gamemaster. This section presents some of the “classic” races and cultures from mythology, literature and fantasy role playing. Each race and culture has a full description in Appendix A-3.

A Gamemaster should determine which races and cultures are appropriate for his world system, as well as incorporating any additional races deemed necessary. A Gamemaster may incorporate other races and cultures into his world using the same factors outlined in this section. An upcoming Rolemaster sourcebook, Cultures & Races, will provide a wider variety of cultures and races.

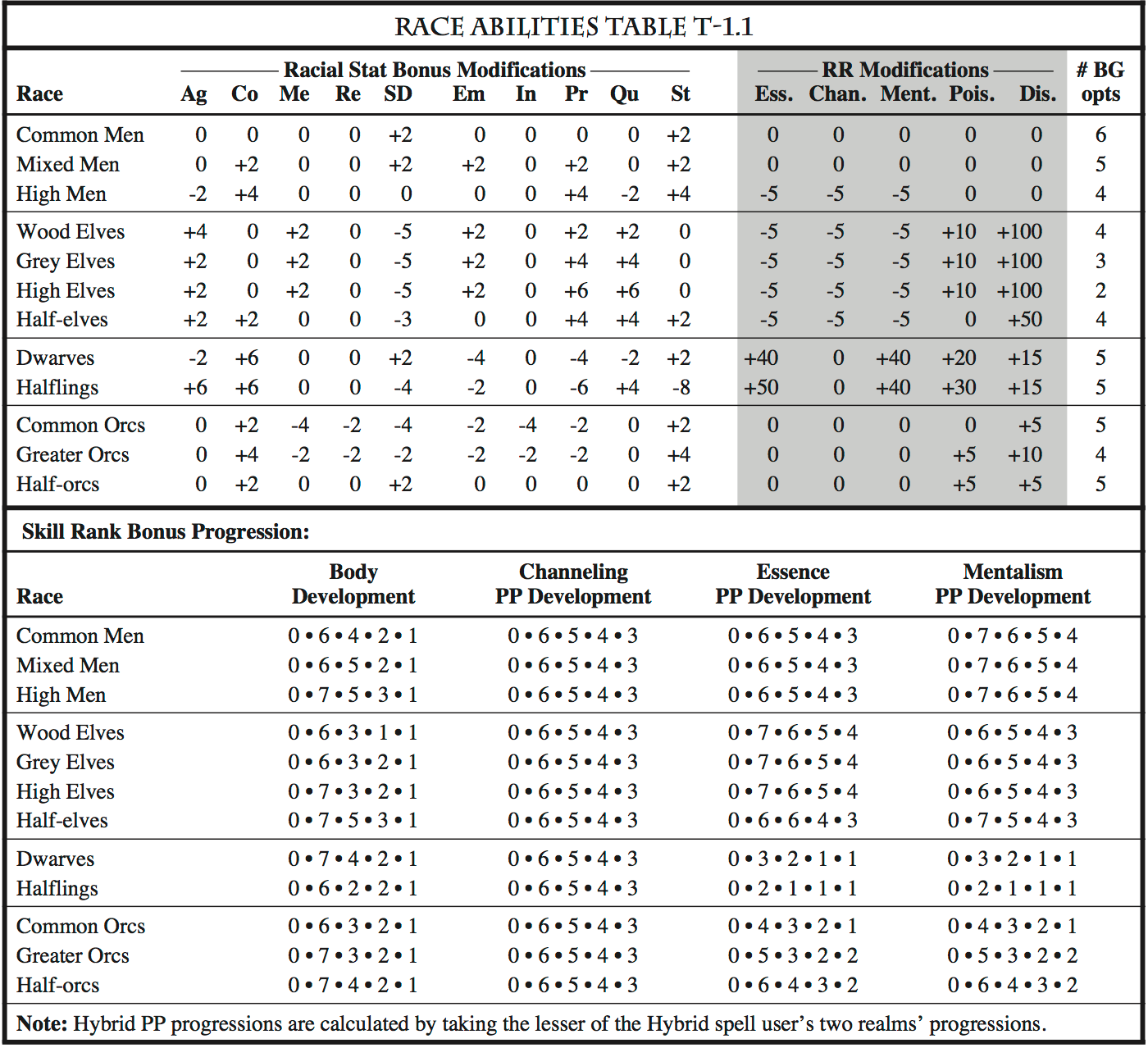

Each character must have a race, and each Common Man and Mixed Man must have a culture. The Race Abilities Table T-1.1 provides the racial abilities and characteristics that influence play in a fantasy role playing game. Section 32.2 provides racial modifications to the effects of death and injury.

Full descriptions for each race can be found in Appendix A-3. The twelve standard Rolemaster races are:

| Common Men | Mixed Men | High Men |

| Wood Elves | Grey Elves | High Elves |

| Half-elves | Dwarves | Halflings |

| Common Orcs | Greater Orcs | Half-orcs |

Each Common Man and Mixed Man character must have a “culture”—one of the six given in Section 3.2 or another culture keyed to the GM’s world.

Each Common Man and Mixed Man character must have a culture. Full descriptions for each culture can be found in Appendix A-3. The six standard Rolemaster cultures are:

| Urbanmen | Ruralmen | Nomads |

| Woodmen | Hillmen | Mariners |

The chief racial factors affecting a character are given in the Race Abilities Table T-1.1:

Stat bonus modifications

Resistance Roll modifications

Body Development skill rank bonus progressions (see Section 6.0 & 8.3)

Power Point Development skill rank bonus progressions (see Sections 8.1 and 8.2)

Background Option information (see Section 14.0)

Certain races will have advantages in certain of these areas, but penalties in others. For example, Elves have better stat bonuses than Common Men but they get fewer Background Options.

Note: Different races also have different modifications to the effects of death and injuries. These modifications are presented in Section 32.2.

The racial racial modifications to stat bonuses apply to the basic stat bonuses described in Section 5.4.

A Resistance Roll modification is added directly to a Resistance Roll (see Sections 8.7 and 21.1) made against an appropriate spell, poison, or disease.

Language can be a unifying element among groups with varying racial or cultural backgrounds. On the other hand, it can also be a barrier which can lead to the destruction of a hearty group of adventurers. Since most worlds embrace a number of tongues, and few characters know all the languages, translators and cooperative efforts may be necessary to solve the language problems. By having each player’s character know and/or understand (to varying degrees) different languages, a tremendous amount of diversity can be injected into the game.

A character’s fluency and literacy in a particular language is determined by the skill rank which the character has achieved in “language” skill for that language (see Section 6.0 and Appendix A-1.12).

The Gamemaster should decide which languages are automatically known by each of the races in his world system. Appendix A-3 provides suggested starting languages and easily learnable languages for each race and culture. Each character may then expand on this base through the skill acquisition process (see Sections 13.0 and 15.0).

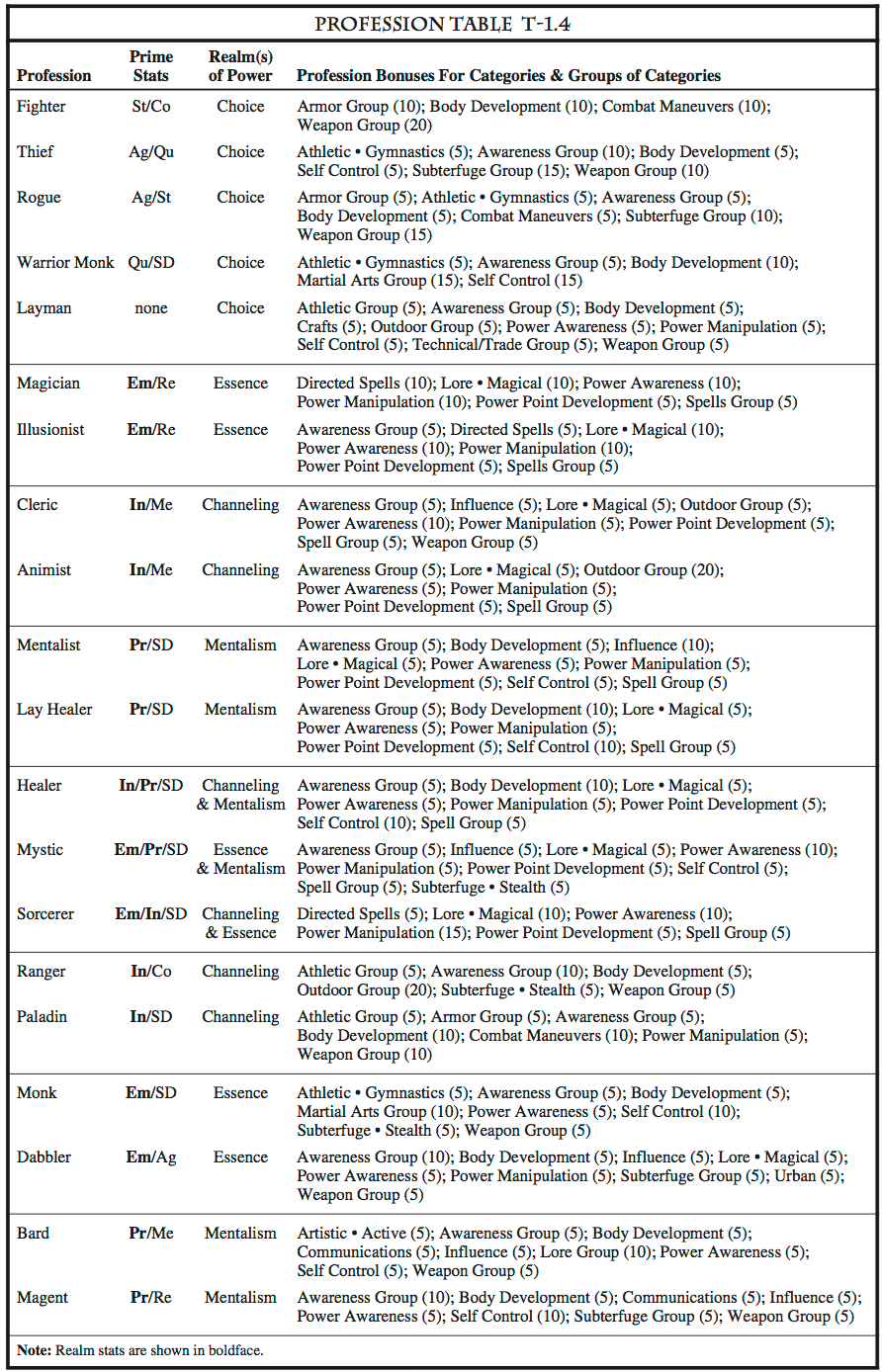

Each character must have a profession. A character’s profession reflects the fact that early training and apprenticeship have molded his thought patterns; affecting his ability to develop certain skills and capabilities. A profession does not prohibit the development of skills, it merely makes some skills harder and others easier to develop. Any character can develop any skill under this system.

Each profession has a full description and specifications in Appendix A-4. Every profession falls into one of six different categories based upon its area of concentration:

| Category | Spell User Type | |

|---|---|---|

| The realm of Channeling | Pure | |

| The realm of Essence | Pure | |

| The realm of Mentalism | Pure | |

| The realm of Arms | Non | |

| Combinations of two realms of power | Hybrid | |

| Combinations of Arms and a realm of power | Semi | |

Professions are classified according to one of four types of spell users: Non spell users, Pure spell users, Hybrid spell users, and Semi spell users. This classification determines a character’s Development Point costs for developing skill ranks for various types of spell lists (see Section 15.2). In addition, Pure spell users get to choose four extra base spell lists (see Section 11.4).

Pure concentrate on one realm of power.

Hybrid concentrate on two realms of power.

Semi concentrate on a realm of power & the realm of Arms.

Non concentrate on the realm of Arms.

For each profession, some of the ten stats are called the profession’s “prime stats.” A character must have at least 90s in each of his prime stats (see Section 12.1).

One the prime stats for each spell using profession is designated as a “realm stat” (two in the case of Hybrids). The stat is Intuition for Channeling users, Empathy for Essence users, and Presence for Mentalism users.

Each profession has fixed “profession” bonuses that apply to certain skill categories (see Section 11.2).

Channeling is the power of the deities of a given world as channeled through their followers or other spell users. It is religious in nature and independent of the Essence. A spell user of Channeling draws directly on the power of his deity, even though this “usually” does not require the conscious cooperation of the deity. Thus spells of this realm do not necessarily reflect the nature of the deity as long as the spell user is using relatively subtle spells (i.e., healing, detection, etc.). More powerful and significant spells such as death spells and the revival of the dead might require the active consent of a deity, depending upon the world system being used by the Gamemaster.

Metal interferes with the drawing of power from deities. So wearing metal armor or a metal helmet may interfere with casting a Channeling spells (see Section 26.0). In addition, only a small amount of metal may be carried on the person of a spell user of Channeling without interfering with casting Channeling spells (see Section 26.0).

Metal interferes with the drawing of power from deities. So wearing metal armor or a metal helmet may interfere with casting a Channeling spells (see Section 26.0). In addition, only a small amount of metal may be carried on the person of a spell user of Channeling without interfering with casting Channeling spells (see Section 26.0).

Cleric and Animist are Pure spell user professions which concentrate primarily on using Channeling power from their deities to create magical effects and cast spells.

Cleric — Clerics are the basic Channeling spell users. Clerics are Pure spell users of Channeling who have concentrated in spells which require direct power from their deities. Their base spells deal directly with life: communing with deities, summoning live creatures, protection from servants of opposing deities, and direct Channeling from their own deities. These spell users are the most powerful of the spell users of Channeling, but they are also the most restricted in the sense of heeding the desires or alignment of their deity (to be determined by the Gamemaster). They have the ability to learn, albeit at heavy cost, the use of any weapon.

Prime Stats: Intuition and Memory.

Animist — Animists are Pure spell users of Channeling (e.g. druids, Shinto priests, etc.) specializing in studies and power concerning living things, both animal and vegetable. Their base spells deal with plants, animals, nature in general and weather. They generally develop the skill of riding (and controlling) animals to a high level.

Prime Stats: Intuition and Memory.

Essence is the power that exists in everyone and everything of and on a given world. It has been known in other sources as the Tao, Magic, Unified Field, the Force etc. A spell user of the Essence taps this power, molds it, and diverts it into spells. Most powerful Essence spells reflect this and are almost elemental in nature: fire, earth, water, wind, light, cold, etc.

The more inert material that is on the person of the spell user of Essence, the more difficult it becomes to manipulation the Essence. Thus, wearing armor, heavy clothing, and a helmet will interfere with the casting of Essence spells (see Section 26.0). In addition, only a small amount of other material may be carried on the person of a spell user of Essence without interfering with casting Essence spells (see Section 26.0).

The more inert material that is on the person of the spell user of Essence, the more difficult it becomes to manipulation the Essence. Thus, wearing armor, heavy clothing, and a helmet will interfere with the casting of Essence spells (see Section 26.0). In addition, only a small amount of other material may be carried on the person of a spell user of Essence without interfering with casting Essence spells (see Section 26.0).

Magician and Illusionist are Pure spell user professions which concentrate primarily on manipulating the Essence that surrounds us all to create magical effects and cast spells. Characters in these professions can acquire knowledge of things magical and how to use them relatively quickly, but they are terribly handicapped in developing arms skills since they must discipline their minds in pursuit of their profession. Like spell users generally, they are less adept than Arms users at the skills of maneuvering and combat.

Magician (Mage) — Magicians are the basic manipulators of the Essence. Magicians are Pure spell users of Essence who have concentrated in the elemental spells. Their base spells deal mainly with the elements earth, water, air, heat, cold and light.

Prime Stats: Empathy and Reasoning.

Illusionist — Illusionists are less able to manipulate the Essence to overpower others, instead developing skills to mislead them. Illusionists are Pure spell users who have concentrated in spells of misdirection and illusion. Their base spells deal mainly with the manipulation of elements which affect the human senses: sight, sound, touch, taste, smell, mental impulses, and the combination of these senses. Illusionists have advantages in perception, stalking, and hiding over other spell users.

Prime Stats: Empathy and Reasoning.

Mentalism is the power of the Essence channeled through the mind of the spell user, who in effect acts as a very, very minor deity for these purposes. Thus, Mentalism is a very personal power, and even the most powerful spells are usually limited by the senses and perceptions of the spell user. Similarly, such spells are usually limited to affecting the caster or one particular target.

Any head covering interferes with the power of Mentalism spells, so wearing helmets will interfere with the casting of Mentalism spells (see Section 26.0).

Any head covering interferes with the power of Mentalism spells, so wearing helmets will interfere with the casting of Mentalism spells (see Section 26.0).

Mentalist and Lay Healer are Pure spell user professions which manipulate their own personal Essence, and the Essence immediately around them with their minds in order to perform magical functions.

Mentalist — Mentalists are the basic spell users of Mentalism who have concentrated on spells which deal with the interaction of minds. Their base spells deal with the detection of mental Presence, mental communication, mind control, mind attack, mind merging, and sense control.

Prime Stats: Presence and Self Discipline.

Lay Healer — Lay Healers can aid the recuperative powers of others. Lay Healers are Pure spell users of Mentalism who have concentrated on spells which heal people and animals. Their base spells deal with the specific healing of certain diseases and injuries: organs, blood, muscles, bones, and concussion hits.

Prime Stats: Presence and Self Discipline.

The professions of Fighter, Thief, Rogue, Warrior Monk, and Layman concentrate primarily on acquiring skill in the realm of Arms. These characters have relatively easy times learning the use of weapons and the skills of maneuver and manipulation, but they will find it difficult to develop spell using ability. These professions have no trained realm of power and thus can only learn spells at great effort and cost (if at all according to the Gamemaster’s discretion). Even then their spells are of very limited potency. If a Non spell user does learn to cast spells, he usually concentrates on spells from one realm—each Non spell user must choose one realm of magic to concentrate on (see Section 11.3).

Fighter (Warrior) — Fighters are the primary arms specialists. Fighters will find it easy to develop a variety of different weapons and to wear heavier types of armor. They are less skilled in maneuvering and manipulating mechanical devices such as locks and traps (though they are still superior in those areas to spell users) and have the greatest difficulty in learning anything connected with spells.

Prime Stats: Constitution and Strength.

Thief (Scout) — Thieves are specialists at maneuvering and manipulating. They have the easiest time learning mechanical skills such as picking locks and disarming traps and are fairly good at picking up weapons skills. Thieves are also unusually adept at stalking, hiding, climbing, and perception. They rarely wear heavy armor, although armor does not especially hinder the exercising of their professional abilities.

Prime Stats: Agility and Quickness.

Rogue — Rogues are characters with some expertise in thiefly abilities and more specialized knowledge of arms than that possessed by Fighters. Normally a Rogue will be almost as good as a Fighter with one weapon of his choice. The cost, in development points, of developing his thiefly skills will generally not allow him to be as good in these areas as a Thief, but his flexibility is unmatched by either profession.

Prime Stats: Agility and Strength.

Warrior Monk (Martial Artist) — Warrior Monks are experts at maneuvering and martial arts. Warrior Monks learn to use normal weapons, although not as easily as others of this realm; they prefer to utilize unarmed combat.

Prime Stats: Quickness and Self Discipline.

Layman (Jack-of-all-trades, Generalist, Everyman, Multifarian) — Normally each character has an “adventuring” profession, reflecting how his early training and life have moulded his thought patterns. However, the Layman profession represents characters who do not have a standard “adventuring” profession. Most non-adventuring NPCs will have the Layman profession.

Prime Stats: None.

Sorcerer, Mystic, and Healer are Hybrid spell user professions, each of which combines some of the powers of two different realms of magic. They can obtain the power of the most potent Pure spell users only in a very restricted set of spells. However, they are much more flexible since they have easy access to two realms of power.

The conditions which interfere with casting spells from each of the three realm (see Sections 26.0) also interfere with a Hybrid spell user casting a spell. For example, a helmet will interfere with casting a Mentalist spell. When casting one of the spells from his base lists, he suffers the interference from both realms.

The conditions which interfere with casting spells from each of the three realm (see Sections 26.0) also interfere with a Hybrid spell user casting a spell. For example, a helmet will interfere with casting a Mentalist spell. When casting one of the spells from his base lists, he suffers the interference from both realms.

Healer — Healers are Hybrid spell users who combine the realms of Channeling and Mentalism; they channel power to take wounds from others and use the enormous recuperative power of their bodies to heal the wounds once taken. Thus, a Healer could heal a person by taking his patient’s injury upon himself and then healing this injury gradually.

Prime Stats: Intuition, Presence, and Self Discipline.

Mystic — Mystics are Hybrid spell users who combine the realms of Essence and Mentalism; they have concentrated on subtle spells of misdirection and modification. Their base spells deal with personal illusion as well as the modification of matter.

Prime Stats: Empathy, Presence, and Self Discipline.

Sorcerer — Sorcerers are Hybrid spell users who combine the realms of Essence and Channeling, concentrating on spells of destruction. Their base spells deal with the specific destruction of animate and inanimate material.

Prime Stats: Empathy, Intuition, and Self Discipline.

Ranger, Paladin, Monk, Dabbler, Bard, and Magent are professions which combine the use of arms with a rudimentary knowledge of spells. These Semi spell users combine a realm of power with the realm of Arms. Normally, these professions can only cast spells of limited potency, but are fairly adept in the use of arms. Generally, these characters are inferior to Fighters in the use of arms and to spell users in the use of spells, but they have the ability to combine the advantages of both to meet a variety of needs.

Ranger — Rangers are Semi spell users who combine the realm of Channeling with the realm of Arms. Their base spells deal with operating in the outdoors and manipulating the element (weather).

Prime Stats: Constitution and Intuition.

Paladin — Paladins are Semi spell users who combine the realm of Channeling with the realm of Arms. Their base spells deal with combat and protections.

Prime Stats: Intuition and Self Discipline.

Monk — Monks are Semi spell users who combine the realm of Essence with the realm of Arms. Their base spells deal with personal movement and the control of their own body and mind, while their arms capabilities are concentrated in unarmored, unarmed combat.

Prime Stats: Empathy and Self Discipline.

Dabbler — Dabblers are Semi spell users who combine the realm of Essence with the realm of Arms. Their base spells deal with stealth, detection, perception, movement, and manipulating locks and traps.

Prime Stats: Empathy and Agility.

Bard — Bards are Semi spell users who combine the realm of Mentalism with the realm of Arms. Their base spells deal with sound, lore, and item use.

Prime Stats: Memory and Presence.

Magent — Magents are Semi spell users who combine the realm of Mentalism with the realm of Arms. Their base spells deal with information gathering and subterfuge.

Prime Stats: Presence and Reasoning.

The base mental and physical attributes of a character are represented by 10 statistics (called stats): 5 “primary” stats and 5 “development” stats. Each character has two numerical values on a scale of 1 to 101 (normally) for each stat (see Section 12.0). The value of a stat indicates how it rates relative to the same stat of other characters. The lower the value of a stat, the weaker it is relative to the same stat of other characters. Relatively high stats give bonuses (see Section 5.4) which apply to attempts to accomplish certain activities and actions.

An individual’s stats represent prowess in various areas in comparison to the average man. John Smith, the townsman, might be theoretically assumed to have stats of 50 across the board. In the primitive society favored for most role playing games, however, it is quite likely that those with stats below 10 will be the first claimed by nature and survivors might tend to have a set of stats that are above the “average” (assume that John Smith has stats of 55). Those with access to better health care (the rich) might tend to live even if weak in critical areas, however. So Noble John Smith’s stats might well average 50.

Adventurers are likely to be superior to the general population. Adventurers are presumed to start with no stat below 20, though the rigors they face may reduce their stats below this level. This is to reflect the fact that weak characters are unlikely to leave the safety of their homes and go out in the world to make their fortunes.

Higher level non-player characters (NPCs) are also likely to be superior to the general population. It is a fact of life that in attempting to increase one’s experience level one has an excellent chance of dying. Superior characters are more likely to survive; thus, in creating and running NPCs, the Gamemaster is urged to consider their experience level when determining their stats.

Each stat has two values: a potential value and a temporary value. The potential value reflects the highest value that the character’s stat can obtain (i.e., due to genetics and/ or early childhood environment). The temporary value represents the stat’s current value. Thus, each character has a set of “temporary” stats and a set of “potentials.”

During play, the temporary stats can rise due to character advancement and other factors and fall due to injury, old age, etc. However, potentials rarely change. Of course, the temporary value for a given stat may never be higher than its potential. Note that a character’s stats do not always increase beyond their starting level: two months of adventuring does not necessarily accomplish what eighteen or more years of youthful exuberance failed to do.

In addition to affecting play, some stats affect the character development process. Agility, Constitution, Memory, Reasoning, and Self Discipline are relevant in determining how many skills a character can learn (development points are equal to the average of these five stats). Note that the five stats above will often be referred to as Development Stats. In game terms, other characteristics do not aid in the acquisition of skills in any way.

Agility (Ag) — Manual dexterity and litheness are the prime components of this characteristic. Also referred to as: dexterity, deftness, manual skill, adroitness, maneuverability, stealth, dodging ability, litheness, etc.

Constitution (Co) — General health and well-being, resistance to disease, and the ability to absorb more damage are all reflected in a character’s Constitution. Also referred to as: health, stamina, endurance, physical resistance, physique, damage resistance, etc.

Memory (Me) — The ability to retain what has previously been encountered and learned. Note that in many instances it may be necessary for the character to rely on the player’s memory, since that tends to be used whenever it is advantageous anyway. Memory provides a good basis for determining how much is retained of the pre-adult period that the Gamemaster doesn’t have time to devise and describe in absolute detail to each player. Also referred to as: intelligence, wisdom, information capacity, mental capacity, recall, retention, recognition, etc.

Reasoning (Re) — Similar to intelligence: the ability to absorb, comprehend, and categorize data for future use. It also reflects the ability to take available information and draw logical conclusions. Also referred to as: intelligence, learning ability, study ability, analysis rating, mental quickness, logic, deductive capacity, wit, judgement, I.Q., etc.

Self Discipline (SD) — The control of mind over body, the ability to push harder in pursuit of some goal, or to draw upon the inner reserves of strength inherent in any individual. Also referred to as: will, alignment, faith, mental strength or mental power, concentration, self control, determination, zeal, etc.

The following characteristics have an influence on direct play, but do not aid in character development.

Empathy (Em) — The relationship of the character to the all-pervading force that is common to all things natural and is the basis of most things supernatural. Also referred to as: emotional capacity, judgement, alignment, wisdom, mana, magical prowess, bardic voice, etc.

Intuition (In) — A combination of luck, genius, precognition, ESP, and the favor of the gods is embodied in this stat. Also referred to as: wisdom, luck, talent, reactive ability (mental), guessing ability, psychic ability, insight, clairvoyance, inspiration, perception, pre-sentiment, etc.

Presence (Pr) — Control of one’s own mind, courage, bearing, self esteem, charisma, outward appearance and the ability to use these to affect and control others are the principal elements of a character’s presence. Also referred to as: appearance, level-headedness, panic resistance, morale, psychic ability, self control, vanity, perceived power, mental discipline, bardic voice, charisma, etc.

Quickness (Qu) — Essentially a measure of reflexes and conscious reaction time, this stat is often lumped with several others as dexterity. Also referred to as: agility, dexterity, speed, reaction ability, readiness, dodging ability, litheness, etc.

Strength (St) — Not brute musculature, but the ability to use existing muscles to their greatest advantage. Also referred to as: power, might, force, stamina, endurance, conditioning, physique, etc.

Certain bonuses and penalties may apply to a character’s skills and activities if his stats are high enough or low enough. These bonuses and penalties are called stat bonuses.

For each stat, a character’s stat bonus is equal to the stat’s basic stat bonus plus its racial stat bonus modification plus any special modifications.:

| Stat Bonus = | basic stat bonus | |

| + racial stat bonus modification | ||

| + special modifications | ||

The basic stat bonuses are determined by the value of each given stat (see the Basic Stat Bonus Table T-2.1), while the racial stat bonus modifications are determined by the character’s race (see Section 3.3). Special modifications come primarily from Talents and Flaws (see Appendix A-5).